This post was originally published on this site

The “Great Resignation,” they call the tens of millions of Americans who’ve quit their jobs. Yet the bigger and better news is the huge number of people being hired.

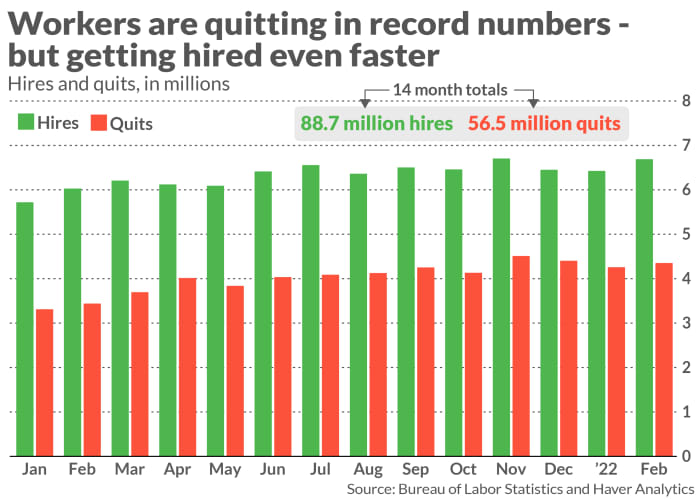

To be sure, Americans have been saying “I quit” in record numbers. Almost 57 million people left jobs — many more than once — in the 14-month period from January 2021 to February 2022. That’s a 25% spike vs. a similar time span before the pandemic.

Yet the overwhelming majority of these job quitters had other jobs lined up or quickly found work elsewhere.

Nearly 89 million people were hired in the past 14 months, government data shows, reflecting a record number of job openings and a ravenous hunger for labor. There’s almost two open jobs for every unemployed person in America.

MarketWatch

“ “People aren’t resigning to sit on the sidelines. The are resigning to take different job.” ”

“People aren’t resigning to sit on the sidelines,” said corporate economist Robert Frick at Navy Federal Credit Union in northern Virginia. “The are resigning to take different job.”

Hiring surge

The hiring wave began more than a year ago. The U.S. added 431,000 new jobs in March, the government said last week, extending a streak of large job gains going back to the start of 2021.

The unemployment rate also sank to 3.6% last month — just a tick above a 53-year-low — from nearly 15% just two years ago.

All of the hiring took place against the backdrop of high covid cases and the reluctance of millions of formerly employed people to return to the labor market. Hiring might have taken place even faster, economists say, if the pandemic had petered out and generous government unemployment benefits were ended sooner.

Read: The U.S. jobs market is scorching hot. Here’s where the flames are highest

Nonetheless, the economy is on track to recover all 22.4 million jobs lost early in the pandemic by early summer. And then start adding even more.

“In hindsight I would not choose the term, ‘The Great Resignation. ‘ It is overly negative,” said senior economist Daniel Zhao of the labor-research firm Glassdoor. “The fact is, people are looking for work and finding work.”

Zhao did not come up with the term, of course, but it’s gained popularity in the media as a way to explain what’s happening in the labor market. But it gives an incomplete picture at best, economists say.

“I have always called ‘The Great Resignation’ a major misnomer,” said chief economist Gregory Daco of EY-Parthenon. “We are in ‘The Great Renegotiation.’ People are quitting for better conditions, pay and flexibility.”

“ “I have always called ‘The Great Resignation’ a major misnomer. We are in ‘The Great Renegotiation.’ ”

Nick Bunker, research director at job-search site Indeed, agreed.

“Resign has this negative connotation,” he said. “It’s more of a ‘Great Job Hop.’ “

Rising wages

Higher pay tells part of the story. Hourly wages began to surge early in the economy recovery — well before the spike in inflation — and they’ve risen at the fastest pace since the early 1980s. Wages have shot up 5.6% in the past year.

By contrast, wages grew an average of just 2.3% a year in the decade preceding the pandemic.

The willingness of companies to offer more flexible arrangements such as remote work also reflects the reality of today’s labor market — one that is likely to survive in post-pandemic times. Many employees, for instance, want to be able to work at home part of the time.

“One thing that is relatively new for the labor market is remote work or flexible work,” Bunker said. “There are people who value that quite a bit.”

What all the flux in the labor market underscore is that employees have leverage over employers for the first time in decades. And they are taking advantage of it.

“Now that employees are looking hard for talent, there are more opportunities to go from one job to another,” said Daco, who is one of those millions of people who’ve switched jobs in the past year.

He left his old job several months ago, Daco said, mainly for a new challenge and the chance to do something different.

Switching careers

The same is true for millions of other Americans. Lots of people have left industries in which face-to-face contact with customers is required, for example, and moved to jobs with less visibility to the public.

Fear of COVID was the biggest reason early on, but the combination of the pandemic and tight labor market has made people reevaluate their careers, analysts say.

Consider leisure and hospitality.

The biggest job losses early in the pandemic took place at restaurants, hotels, theaters and the like that cater to large crowds. Even now, employment in the sector is still 1.8 million below its record peak of almost 17 million.

Where did these workers go? Many ended up at transportation or professional jobs with little direct exposure to the public.

The number of people employed by transportation and warehouse companies — think UPS

UPS,

or Amazon

AMZN,

— has jumped to 6.4 million from 5.8 million before the pandemic. Job gains have been even larger at white-collar businesses.

“This is not just about replacing jobs that were lost during the pandemic,” said Zhao, pointing to rising employment in transportation. “Clearly there are new jobs being created.”

How long can all the quitting and job-hopping go on?

As long as the economy is expanding, the labor market remains tight and companies have to compete aggressively for workers.

“ “If we are saying the Great Resignation is a result of the hot jobs market, we should expect lots of resignations to continue so long as job openings are high.””

“If we are saying the Great Resignation is a result of the hot jobs market, we should expect lots of resignations to continue so long as job openings are high,” Zhao said.

Worker power

What’s less clear is how long the surge in wages will last.

More people are expected to return to the labor force, for one thing, and ease the upward pressure on wages. Companies are also investing extra in automation, either as a substitute for labor or to help make workers more productive.

Don’t expect wage growth to slow to precrisis levels anytime soon, however. Not with such a tight labor market and U.S. inflation running at a 40-year high. Workers are likely to keep asking for more money.

“From an employers point of view this is very disappointing,” Frick said. “From an employees point of view, it’s great. They have more power.”