This post was originally published on this site

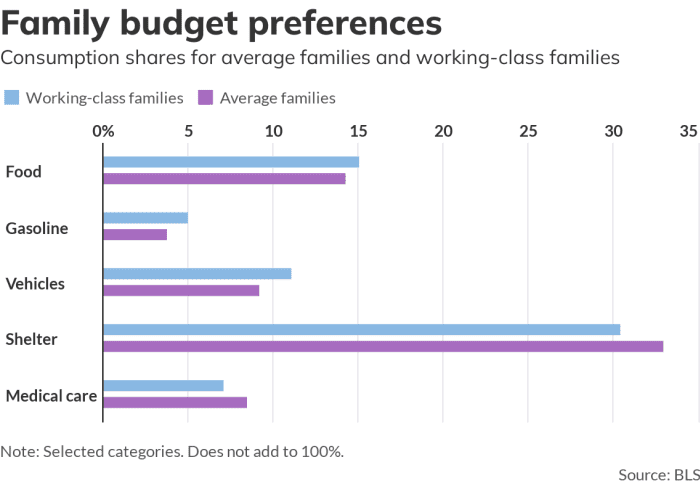

America’s working class is getting clobbered by inflation because wage earners spend a larger share of their income on the things that are going up in price the most, especially necessities such as food, gasoline, and cars and trucks.

The CPI-W — an inflation gauge that corresponds with the consumption habits of working people — has risen 9.4% in the past 12 months, compared with an 8.5% increase in the CPI-U, an inflation measure that considers the habits of a broader swath of American households, including retirees, investors and working people who earn salaries.

Follow the full inflation story on MarketWatch.

The difference between an inflation rate of 9.4% and one of 8.5% can be explained entirely by the fact that the working class spends relatively more on food, gas and used car and trucks. Spending on those three categories accounts for less than 25% of the working family budget, but 51% of the inflation they’ve experienced over tyhe past year. (My thanks to Labor Department economist Steve Reed for tutoring me on these calculations.)

News: Peak inflation? The worst may be over, but Americans to keep paying a high price

The disparity between working-class inflation and average inflation is the highest on record — and it’s been getting wider in recent months. Over the past six months, inflation for the working class has risen at an 11.1% annual rate compared with 10.1% for the general consumer price index.

What is the CPI-W?

Each month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports on two versions of the consumer price index. Both versions start with the same survey of prices for hundreds of goods and services collected at thousands of business around the country.

The version that most people hear about — the CPI-U — assigns a relative importance to each item that corresponds with how much the average American household buys. The CPI-U covers about 93% of U.S. households.

The CPI-W, on the other hand, assigns weights to each item according to how much a typical working-class household buys. The CPI-W covers about 29% of households, focusing on families that rely on wage income from certain occupations, such as clerical work, sales, production and construction. The CPI-W is best known for its role in determining cost-of-living increases for Social Security recipients.

Most of the time, the inflation rate for the two versions is quite similar, but sometimes a gap forms between the inflation experience of workers and everyone else.

Like now.

Wage workers and their families spend relatively more of their budget on food, gas and vehicles, and less on shelter and medical care. Those spending preferences are responsible for the unequal way different families experience inflation.

Energy supplies

What’s behind the growing disparity? It’s mostly because energy prices

CL00,

have surged over the past year as booming global demand has outpaced global supplies. The Russian war against Ukraine has cut sharply into actual and expected supplies of natural gas and petroleum, boosting prices even further.

Higher energy prices have hit the working class hard. Working-class families spend 9% of their monthly budget on energy, compared with 7.4% for the average family. They spend 5% of their income on gasoline

RB00,

compared with 3.7% for typical families. That may not seem like much of a difference, but when gasoline prices rise 18% in one month and 48% in a year, the impact of buying just a few more gallons a month begins to bite.

Working-class families spend relatively more on food, new and used vehicles, rent, utilities, tobacco and clothing. They spend relatively less on homeownership, hotels, medical care, alcohol, education and airfares.

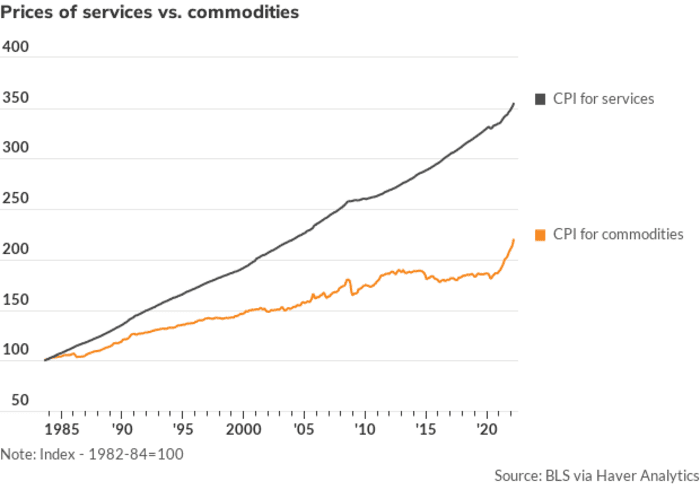

Until the pandemic hit, prices of services were rising about twice as fast as prices of commodities.

MarketWatch

Goods versus services

Another way of putting it: Working families spend a greater share of their budget on commodities (physical goods) than the average family does: 43% to 39%.

For decades, this preference for commodities was a positive for the working class from an inflation perspective, because commodity prices were generally rising more slowly than the prices of services were. From 1980 to 2020, commodity prices rose at an average annual rate of 2%, while services rose 3.8%.

Cheap imports and technology were the main drivers of that slow rise in commodity prices. The flip side: Employment in goods-producing industries was severely shaken by the relative decline of goods production in the U.S. while millions of jobs were created in relatively low-paying services.

Since the pandemic hit, however, commodity prices are up at an 8.3% annual rate, while services have risen just 3.3%.

Prices of durable goods, in particular, had been falling for decades, benefiting working families who spent relatively more on motor vehicles, appliances, electronics and tools. Prices of durable goods fell by a cumulative 20% from 1996 to 2020. But since then, they’re up 21%, nearly erasing 25 years of falling prices.

The pandemic severely disrupted supply chains of durable goods and other commodities (including gasoline, fertilizer and agricultural products). Services were less affected by the supply-chain troubles, because most services don’t rely on distant suppliers but upon local labor and suppliers.

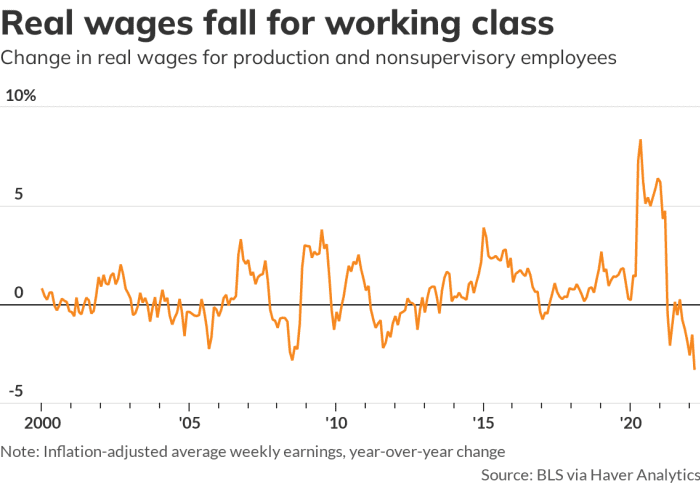

The purchasing power of wages is falling for the working class at the fastest pace in more than 30 years.

MarketWatch

Inflation erases wage gains

There’s one mitigating factor that is benefiting working-class families: The strong labor market. Employment is up by 6.5 million in the past year. Working-class weekly paychecks have risen faster than others’ earnings have, but the higher inflation rate for workers has eaten away at those gains and then some. Real average weekly wages have fallen 3.3% for the working class in the past year, the biggest decline in more than 30 years.

It’s the same grim story for real median wages. Through the fourth-quarter of 2021, median wages adjusted for CPI-W inflation were down 4.5%, near a 42-year low.

Rex Nutting has written about economics and politics for MarketWatch for more than 25 years.

More on inflation

High inflation places more of a burden on working families, Fed Gov. Brainard says

Opinion: Inflation inequality: Poorest Americans are hit hardest by soaring prices on necessities