This post was originally published on this site

Representation is what motivates Shameka Lee.

Lee, 46, is the interim manager of the Oklahoma City Action Center, a call center akin to what’s sometimes called 311 in other cities. She started as a temp seven years ago and has grown into her current role, a process she calls “the whole purpose” of any career.

As she has advanced, Lee has taken Spanish lessons. “We want to be able to reach people who don’t speak English,” she said in an interview. “Let me tell you, you have a problem and you’re calling your government and no one understands you — that’s scary. I want all our residents and employees, 10 years from now, to see a reflection of themselves. I want them to feel part of the whole.”

The empathy Lee brings to her work isn’t always reciprocated. “I’m an African-American. I think about race all the time,” she said. “I live in a world where I’m not always expected.”

But she has had excellent managers, she said, and has always felt her workplace was “fair.” Lee also appreciates that Oklahoma City recently launched a diversity and inclusion initiative. “When you see the city trying, you want to jump on board and help with that,” she said. “We’re moving forward.”

‘I want all our residents and employees, 10 years from now, to see a reflection of themselves,’ says Shameka Lee.

Courtesy of Shameka Lee

To some extent, Oklahoma City’s efforts toward a more diverse workplace, and one that especially welcomes Black workers, aren’t anything new. Black workers have long made up a bigger share of the state and local government workforce than the private sector, largely because of intentional civil rights-era policies and initiatives designed to open up more opportunities and enable advancement for them. And government work at all levels has been associated with reducing the Black-white wealth gap and helping create the Black middle class of the 20th century.

But as with so many things in American society, the shocks of the past two years are putting that history to the test.

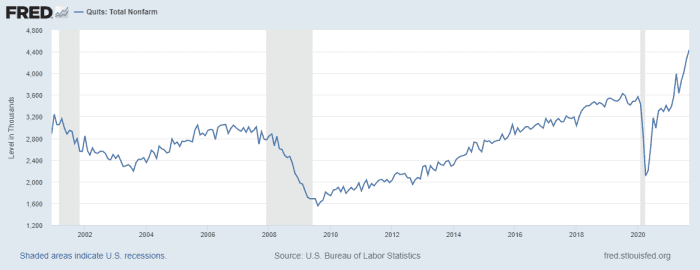

In the early months of the COVID-19 crisis, state and local governments slashed 1.3 million jobs. Eighteen months on, not even half have been refilled. Meanwhile, every month for the past six has seen a fresh record number of Americans overall quitting their jobs, in many cases because they’re fed up with poor wages and working conditions — or are just hungry for something different.

St. Louis Fed, Labor Department

The shifts in the workforce come as the country reckons with ongoing violence against Black men and women, and backlash against the teaching of America’s racial history. Meanwhile, trust in local government now sits at its lowest in over two decades, according to a recent Gallup poll.

Taken together, this all suggests a very different future from the compact that has existed between Black municipal workers and their communities over the last several decades.

“I think this might be a moment where people are exploring. Are people resigning because they want more money? More meaning in their careers?” said Hughey Newsome, who as chief financial officer for Wayne County, Mich., helps manage a budget of roughly $1.7 billion. “I don’t know the answer, but I think there is an opportunity here because there is a big question mark. People are looking for something.”

Newsome, who is Black, knows a bit about “looking for something” in a career: He left a comfortable job in management consulting to become the CFO of Flint, Mich., at the height of the city’s water crisis. Now he thinks the country is at a crossroads.

“At the national level, public service has not done a good job of advertising itself,” he told MarketWatch. “Most young people are probably looking at the profession, seeing all the nastiness and superimposing it to the local level. The polarization, lack of civility — that kind of infects how people see all of public service. It’s a sad state of affairs, because this is the opportunity we have to shine now.”

‘Good, equitable jobs’

Over the first 12 months of the pandemic, the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute published a series of analyses showing how public-sector layoffs would disproportionately impact workers of color.

“One in five state and local government workers is a woman of color (19.9%, compared with 18.2% in the private sector),” the group wrote. Black women make up 8.7% of the municipal workforce versus just 6.4% of the private sector, and Black workers overall account for nearly one in seven state and local government employees, compared to fewer than one in eight private-sector employees.

The sector “has been a really important employer for Black workers and women,” Julia Wolfe, a state economic analyst with EPI, told MarketWatch.

“This isn’t a coincidence. It’s come about because of intentional policy choices that have made these good, equitable jobs,” Wolfe said. “There’s been a lot of intentionality behind making sure the government is a more equitable employer at the outset, making sure they’re reaching a broader pool of candidates.”

Public-sector workers are also unionized at much higher rates than the private-sector workforce is, Wolfe noted — another way to ensure more fairness and equity in hiring, compensation and upward mobility.

As a 2020 analysis from the liberal Center for American Progress put it, “Public jobs provide good wages, better benefits, and greater job security, all of which are critical components of economic security and help families build wealth.”

That has helped narrow the racial wealth gap among those who work in the public sector, where white households hold roughly $2 for every $1 of wealth for Black families, versus in the private sector, where white households have as much as $10 of wealth for each $1 Black households hold.

‘The only’ or ‘the first’

For all that, sources who spoke with MarketWatch described often having to blaze their own trails.

“I started my city management career in 1989, and of course you’re the first woman of color in every position you’re always in. So I always felt a responsibility to make sure every jurisdiction had outreach,” said Valerie Lemmie.

Lemmie, who is currently the director of a foundation after nearly four decades in public service, including as the city manager for Petersburg, Va., and Dayton and Cincinnati, Ohio, says there was no one to mentor her.

Valerie Lemmie presents the mayor of Fort Wayne with an All-American City Award in August.

Courtesy of Valerie Lemmie

“First of all, you’re the boss, so it’s hard to be nurtured. They expect you to lead and guide and not be vulnerable,” Lemmie said. “My first job in Petersburg, the editorial in the local paper the first day said, ‘When she was hired she was Superwoman, and now that she’s here, she’s fair game.’”

Marcia Conner is the executive director of the National Forum for Black Public Administrators, a national organization founded in 1983 by a group of city managers of color who “felt like they needed a group of like-minded individuals they could bond with in terms of being ‘the only,’ or ‘the first,’” she said.

“What we’re seeing is definitely an increase in the number of African-Americans being hired in positions around the country,” Conner told MarketWatch, “but of course we are still not the majority of the ones being hired.”

Like many others, Conner believes representation at higher levels of municipal government is important. “People like to see people who look like them leading,” she said. “There’s empathy there in terms of needs.”

To that end, the organization is stepping up recruitment efforts. “We continue to say to those looking for careers, there are great opportunities, great benefits and environments to work in,” Conner said. “We need to do a better job of using people in the community who are not as skilled and not as well-trained.”

That may have been a hard sell even before the shocks of 2020. Now, some local-government champions worry about the tarnished appeal of going to work for a government that doesn’t appear to work for its people.

“We have a sense of skepticism and mistrust, which is healthy in a democracy because it means people will be held accountable as they should be,” Lemmie said. “I think that the pressure this generation has put on institutions is necessary. Many young people feel that public institutions tend to be more partisan, so they look to nonprofits instead. My counsel is that you need change from within and without.”

‘You’ve got to be intentional’ about recruitment

Thirty years after Lemmie began her public-service tenure, LaShawn Thompson isn’t “the first,” but she is “the only minority in the executive level in the city,” she said.

Thompson, the municipal courts administrator for Oklahoma City, is not the only person of color in leadership: Her husband is a battalion chief in the fire department, and the head of the diversity and inclusion initiative mentioned earlier by Lee is a high-ranking manager.

LaShawn Thompson is the municipal courts administrator for Oklahoma City.

Courtesy of LaShawn Thompson

Still, Thompson told MarketWatch, “My colleagues are great. But it does feel like there is not anyone that I can identify with. I’m treated equally, but I would like to see some other representation at the table.”

Thompson has recently taken on more recruitment efforts herself, recognizing it’s hard for many people, particularly younger ones, to grasp all the moving parts that go into running a city — as well as all the opportunity that affords.

“You’ve got to be intentional,” she said. “You can’t just sit at the table without doing anything. We have to care about what the world looks like behind us.”

Newsome, the Wayne County, Mich., CFO, put it more bluntly.

“It’s sexier to try to change things from the outside,” he said. “At the end of the day I have to deliver a balanced budget, deliver the annual audit. If you want to save the world and be green, that’s fine, but [in city government] you still have to manage the park or make sure we do an environmental assessment of our drains. The day-to-day is the primary focus.”

Newsome sees an opportunity for the federal government. President Biden’s White House has expressed a desire to foster diversity, equity and inclusion in the federal workforce, and advance racial justice more broadly, he noted.

But Thompson thinks the influence may better come from closer to home.

“I think it’s going to be an attitude of ‘I see Ms. Thompson, Chief Thompson, but I don’t see the trajectory of how they got there,’” she said. “I think if we continue to steer our children to local government, they can see the blessings.”