This post was originally published on this site

Some analysts warn that 2022 will be a difficult year for commodities, with the economic impact of the pandemic likely to result in more volatility after this year’s rally in energy prices fed inflation but also prompted expectations of higher interest rates that pressured metals metals.

“It will be a more challenging year for commodities in 2022 because global central banks are tightening policy,” says Noel Dixon, global macro strategist for State Street.

“Central banks reacting to supply-driven inflation,” which they cannot control, is “likely to result in a policy mistake that will adversely impact demand,” he says.

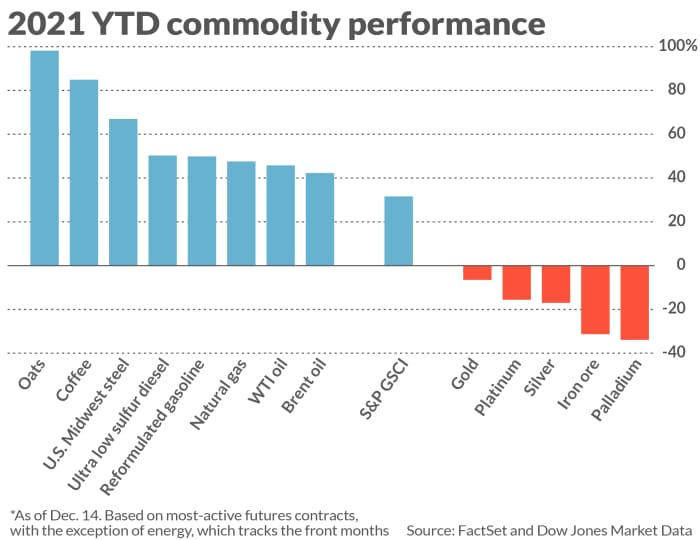

Overall, commodities performed well this year. The S&P GSCI

XX:SPGSCI,

a commodity index composed of 24 exchange-traded futures contracts across five physical commodities sectors, is up more than 32% as of Dec. 14, on track for its largest yearly percentage rise in 12 years.

Commodities “once again proved their value” this year, and demand “appears to be growing for almost all commodity markets, while supply is structurally constrained across the board,” says Hakan Kaya, senior portfolio manager at Neuberger Berman.

Leading the rise, the S&P GSCI Energy index

XX:SPGSEN

has gained 48%. S&P GSCI subindexes for industrial metals

XX:SPGSIN,

agriculture

XX:SPGSAG,

and livestock

XX:SPGSLV

have also climbed.

In general for the commodities that saw the biggest gains this year, low inventories and reduced capital expenditures led to concerns as to whether supply will be “adequate to match resurgent demand,” says Eliot Geller, partner at CoreCommodity Management.

This led to higher prices and many of the “favorable factors” that contributed to the rally “such as inflation, supply-constrained physical markets, commodity-intensive infrastructure spending, rising production costs, and the ongoing transition to a lower carbon economy are expected to persist, and in some cases, accelerate in 2022,” he says.

Precious metals decline

Still, the S&P GSCI Precious Metals

XX:SPGSPM

index is down nearly 7%, defying the upward trend among the other S&P GSCI subindexes this year.

“As global central banks have begun to tighten, it has caused gold to underperform as real yields have increased,” says Dixon. As of Dec. 14, gold futures

GC00

traded more than 6% lower this year, while silver

SI00

has lost 17%.

Read The tale of two metals: why copper and silver have taken split paths this year

Gold’s performance in 2022 will depend largely on how the omicron variant affects the global economy and trade, says Geetesh Bhardwaj, director of research at SummerHaven Investment Management. “With inflation remaining stickier than the Fed had hoped, any loss of confidence in growth prospects could be very bullish for gold.”

On Dec. 15, the U.S. Federal Reserve said it would phase out its bond-buying stimulus program sooner than previously planned, and suggested three interest-rate hikes next year as it moves to fight high inflation.

Meanwhile, Taylor McKenna, analyst at Kopernik Global Investors, points out that gold’s decline this year comes despite the highest inflation in decades, and the market has not seen major new gold mines being built for many years. Even though commodities, with the exception of precious metals, have been performing well, mining companies are “still shunned by the market,” he says.

Gold is among the commodities trading below “where the long-run fundamentals suggest they should trade,” says McKenna, adding that Kopernik estimates gold’s “fair” price at around $2,000. “We see upside if gold stays at current prices and tremendous upside should gold increase” to our fair price estimates.

Also see: Platinum, palladium buck an overall upward trend for commodities, poised for hefty 2021 losses

Energy rally

In the energy market, natural-gas futures

NGF22

NG00

lost nearly 40% in the fourth quarter, but they are still ready to post a yearly rise of 49% on the back of strong liquefied natural gas demand from Europe and Asia, curtailed flows from Russia to the European Union, and “restrained” U.S. production, says CoreCommodity’s Geller.

Read: Why consumers will be paying a lot more for natural gas this winter

Oil, meanwhile, made a strong comeback from the historic April 2020 drop in U.S. benchmark prices to less than zero dollars a barrel. West Texas Intermediate crude futures

CLF22

CL

trade about 47% higher this year, but demand uncertainty, tied to the spread of the delta and omicron variants of coronavirus, was a key reason why major oil producers known as OPEC+ decided to keep its December meeting open to make adjustments to their oil production agreement.

Dixon said State Street is “neutral” on the price outlook for oil as the market deals with “the juxtaposition of slower growth and lower supply as shale producers refuse to increase output due to regulation and uncertainty surrounding demand.”

Still, there is more of an upside risk as these supply constraints from shale producers can get “exacerbated” as Covid adds to demand uncertainty, and with questions surrounding OPEC+ spare oil output capacity, he says. The International Energy Agency estimates 5.1 million barrels per day in spare OPEC+ output capacity by the end of 2022, but the number is likely “too aggressive,” he says.

The natural-gas market is expected to remain tight, and prices are likely to move up, next year, says Dixon. The euro zone, which suffered from an energy crisis this year, is set to drive price moves “as the major suppliers are still at capacity.”

Commodity standouts

Among agricultural commodities, oats

OH22

saw the largest percentage gain — about 96% this year — while coffee futures

KCH22

trade 85% higher. Relatively high prices for other grains led U.S. farmers to plant less oats, and key regions such as North Dakota and the Canadian Prairies experienced very dry weather, Dixon says. For coffee, “the worst frost seen in decades devastated Brazilian crops and yield potential for some time to come,” he says.

Also see: MarketWatch’s Western Drought Watch coverage

Meanwhile, the disconnect between a rise in steel and fall in iron-ore prices is “puzzling,” he says. Legacy tariffs imposed by the Trump administration on imported steel, and pent-up demand may be to blame for higher steel prices, he says. U.S. Midwest domestic hot-rolled coil steel futures

HRNF22

are up 67% year to date. Dixon says steel prices are likely to decline next year, given a “given a move back to trend growth globally.”

Speculation, however, is likely behind this year’s fall for iron ore given concerns around tensions between China and Australia, the largest exporter of iron ore, says Dixon. A financial crisis at Chinese property giant Evergrande also fed worries about the economy and a potential demand decline for raw materials. Futures for 62% iron-ore fines delivered to China

TIOF22

have lost around 30% this year.

Read: Commodities, including iron ore and copper, take a hit on potential collapse of China’s Evergrande

State Street is “neutral” on the outlook for iron ore, given recent news that China will boost economic fiscal support, but “this may not be priced in,” says Dixon. Even so, any support from that factor would be “limited in scope.”

Commodity drivers for 2022

While some of the headwinds for commodities next year include demand shocks if consumer or business restrictions are imposed again due to the spread of the omicron variant and if China’s economic growth slows further, SummerHaven is bullish on commodities long term, as “transformational energy technologies, infrastructure investment, and climate policy” looks to drive the commodities markets, says Bhardwaj.

But the “real risk” for commodities will be demand, says Neuberger Berman’s Kaya. Federal Reserve tapering of asset purchases and rising interest rates are not likely to significantly “make us drive, eat, or consume less,” he says, and another mutation of Covid-19, “with more transmission and hospitalization rates may not kill demand, but certainly has the potential to delay it.”