This post was originally published on this site

Zoom Video Communications Inc. confirmed on Thursday that it complied with a Chinese government demand in suspending the accounts of three U.S.- and Hong Kong-based human rights activists for hosting Zoom events to commemorate the anniversary of Beijing’s violent suppression of demonstrators in and around Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Zoom said it suspended the paid account of a U.S.-based Chinese dissident group, Humanitarian China, as well as the accounts of Lee Cheuk-yan, the Hong Kong-based organizer of the region’s annual Tiananmen vigil, and Wang Dan, a U.S.-based Tiananmen activist. All three accounts have been reinstated.

“In May and early June, we were notified by the Chinese government about four large, public June 4th commemoration meetings on Zoom,” the company said in a Thursday blog post. “The Chinese government informed us that this activity is illegal in China and demanded that Zoom terminate the meetings and host accounts.”

Zoom said it had been contacted by the Chinese government in May and early June about four online meetings related to the Tiananmen Square crackdown that had been publicized on social media. Zoom reviewed the meetings’ metadata—from the U.S.—and confirmed from IP addresses that several participants would be calling from China’s mainland. The accounts hosting the events were not registered in mainland China.

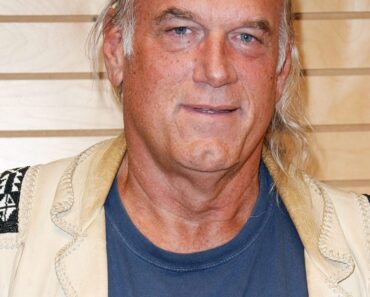

“I’m very angry of course, that even in this country, in the United States … we have to be prepared for this kind of censorship,” Zhou Fengsuo, who founded the U.S. nonprofit group whose account Zoom suspended, told the South China Morning Post. Zhou was a prominent student organizer in Beijing in 1989. He served a year in prison after the crackdown, has lived in exile in the U.S. since 1995, and is now a U.S. citizen.

Zoom said it “fell short” by suspending accounts based outside of mainland China in aiming to “comply with local laws.”

“Our response should not have impacted users outside of mainland China,” Zoom said in the Thursday statement. The company promised that, in the future, Zoom users outside China’s mainland would not be affected by Chinese government requests.

Global lockdowns to slow the spread of the coronavirus have proved a huge boon for NASDAQ-listed Zoom, driving the number of its daily users above 300 million—and its share price into the stratosphere. Zoom’s chat service has become a key work-from-home tool for businesses, schools, and universities around the world, including China which boasts, by far, the world’s largest online population with an estimated 840 million Internet users.

Eric Yuan, Zoom’s founder and CEO, was born in China. He is a U.S. citizen, and launched Zoom after years as a senior engineer at Cisco Systems video conferencing unit Webex.

In China, the company has operated a censored, localized version of their video chat service since September when Beijing blocked the global version. About a third of Zoom’s developers are based there.

Beijing has erected an elaborate system of rules and technologies, often called the Great Firewall of China, to censor and monitor the dissemination of online information within its borders. In May, Zoom changed its policy in China so that unregistered users could join, but not host Zoom meetings. Mainland China users who want to host must buy a license from the company, a move seen as further compliance with Chinese government Internet controls.

Zoom said it will continue to comply with government requests within China. The company is developing technology that will enable it to remove or block any participant in a Zoom call, based on the participant’s location, so that it will be able to “comply with requests from local authorities when they determine activity on our platform is illegal within their borders[.]”

Lee, the Hong Kong activist whose account was suspended, said he wanted a refund for his Zoom subscription and called for a boycott of the company. “What we are opposing is political censorship,” he told Hong Kong broadcasting service RTHK on Friday. “It’s very obvious [Zoom is] kowtowing to the pressure from China.”

Zoom’s efforts to comply with Beijing’s demand drew sharp criticism from U.S. legislators. Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) wrote a letter to Yuan telling the executive to “pick a side” between “American principles and free speech, or short-term global profits and censorship.” Rep. Greg Walden (R-Ore.) and Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.) also wrote a letter to Yuan asking him to share details of whether user data was shared with Beijing and whether Zoom encrypted users’ communications.

The Zoom saga follows a long string of American Internet companies that have grappled with how to adapt their U.S.-based platforms to China’s heavy-handed censors without losing either market.

Most—if not all—have stumbled in that balancing act—abandoning one market for the other or building clones of their flagship tools to appease Beijing. Zoom, still a relative newcomer, is learning the lessons of its predecessors the hard way.

Zhou, the Tiananmen activist and Humanitarian China founder, has been the subject of previous tech run-ins with Beijing.

In 2019, LinkedIn, which is owned by Microsoft, censored Zhou’s profile on the platform, explaining in a message that his page would no longer be viewable in China “due to the presence of specific content.”

“While we strongly support freedom of expression, we recognized when we launched that we would need to adhere to the requirements of the Chinese government in order to operate in China,” Linkedin said in its message to Zhou. The company later restored Zhou’s profile after public outcry and apologized, calling the move “a mistake” and saying the profile had been “blocked in error.”

Zhou’s profile is blocked on Linkedin China, the localized version of the website available in mainland China that the company launched in 2014.

Linkedin continues to operate its Chinese-language in China as one of the few unblocked international Internet companies, thanks to its willingness to abide by the country’s censorship requirements—it will remove any posts or profiles the Chinese government deems politically sensitive.

Yahoo

In 2004, Chinese journalist Shi Tao leaked a government-issued document with censorship instructions for the upcoming June 4 anniversary to a U.S.-based website, emailing it via a Yahoo account. The website, Democracy Forum, uploaded the document as an anonymous post, but Yahoo provided the Chinese government with evidence that Shi had sent the email.

Chinese authorities arrested Shi in Dec. 2004, and in June 2005, the Changsha Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Shi to 10 years in prison for sharing the document, accusing him of “illegally providing state secrets to foreigners.”

Another dissident, Wang Xiaoning, brought a lawsuit against Yahoo in 2007, while serving a 10-year prison sentence in China. Wang accused the company of helping Chinese authorities identify and torture political dissidents, including Shi Tao and himself. Yahoo settled the lawsuit that year.

“To be doing business in China, or anywhere else in the world, we have to comply with local law,” Yahoo co-founder and then-CEO Jerry Yang said in 2005. Yang later testified in front of the U.S. Congress about Yahoo’s role in the dissidents’ arrests, and apologized to Shi’s mother, who was present at the hearing.

Yahoo invested $1 billion for 30% of Alibaba in 2005, and Alibaba bought and operated Yahoo’s China domain, Yahoo.cn, which journalism advocacy group Reporters Without Borders in 2006 said had stricter censors than any other search engine in China.

Yang stepped down as CEO of Yahoo in 2009. In 2012, Yang resigned from Yahoo’s board of directors and also resigned from the boards of Yahoo Japan and Alibaba Group.

Yahoo in 2012 offloaded a significant portion of its China assets when it sold half its stake back to Alibaba in 2012. Yahoo offloaded its remaining Asian assets in 2019 when Altaba, the spin-out created in 2017 to house Yahoo’s remaining Alibaba stake, sold its 15% stake in Alibaba and 35.5% stake in Yahoo Japan.

TikTok

TikTok, a short video platform that is wildly popular in the U.S., is owned by Beijing-based tech company ByteDance, which operates a separate version of the app called Douyin for the China market.

In November, TikTok locked the account of an American teenager who posted a video criticizing the Chinese government’s treatment of Muslims in China. The company later apologized and reversed the account ban, calling it a “human moderation error.” A leaked document obtained by the Guardian last year showed that TikTok moderators had instructions to censor videos that mention politically-sensitive topics in China like the Tiananmen protests and Tibetan independence, undercutting TikTok U.S. claims that it doesn’t censor content on the platform.

ByteDance’s assurances that TikTok is run separately from its Chinese counterpart have been greeted with skepticism from U.S. authorities, who have held congressional hearings to discuss whether TikTok, which has offices in the U.S., is a national security threat.

Google was blocked in China on and off throughout the 2000s. A censored version of Google, Google.cn, launched in 2006 and was available in China until 2010, when it was shut down over censorship disputes. Google and Google-related apps like Gmail, Blogspot, and Google Maps have been largely unavailable in China since then. Youtube, a subsidiary of Google, is also blocked in China.

In 2018, the Intercept obtained leaked documents and reported that Google was planning to launch a new censored version of its search engine for China codenamed Dragonfly, that would automatically blacklist websites and search terms already blocked by the “Great Firewall,” China’s government web censors.

Google said in 2019 that it had “terminated” the Dragonfly project. Google employees had publicly protested the project for months after it was revealed in 2018, and over a thousand employees signed an open letter calling for the cancellation of the project, which they said would enable state surveillance and help the Chinese government “repress dissent.”

Facebook has been blocked in China since 2009, following ethnic unrest and riots in Urumqi, Xinjiang and reports that protestors were using Facebook to communicate. Twitter was also blocked after the riots, as government censors moved to stanch the flow of information in China about the unrest.

Facebook-owned Instagram was blocked in 2014, in the midst of Hong Kong’s “Umbrella Movement” protests, reportedly to prevent the pro-democracy message of the movement spreading to the mainland.

Facebook’s Whatsapp was blocked in 2017, weeks before a large Communist Party gathering—a common move by Chinese government censors to limit and monitor discussion of sensitive topics and ensure important political events run smoothly.

Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s founder and chief executive, has long and unsuccessfully courted Beijing, in an attempt to gain access to China’s Internet. Zuckerberg has made public his efforts to learn Mandarin, taken jogs through the Beijing smog, recommended Xi Jinping’s book to his employees, and even asked the Chinese leader to help name his unborn daughter. Facebook and its subsidiaries remain blocked in China.

More must-read international coverage from Fortune:

- New research shows how face masks can stop second and third coronavirus waves

- Mike Pompeo says HSBC saga shows what happens when business supports Beijing

- Europe’s internal borders are opening again—but not fast enough, says the European Commission

- All the job cuts each airline has announced so far

- WATCH: The global crisis in recycling

- Subscribe to Fortune’s Eastworld newsletter for expert insight on what’s dominating business in Asia.