This post was originally published on this site

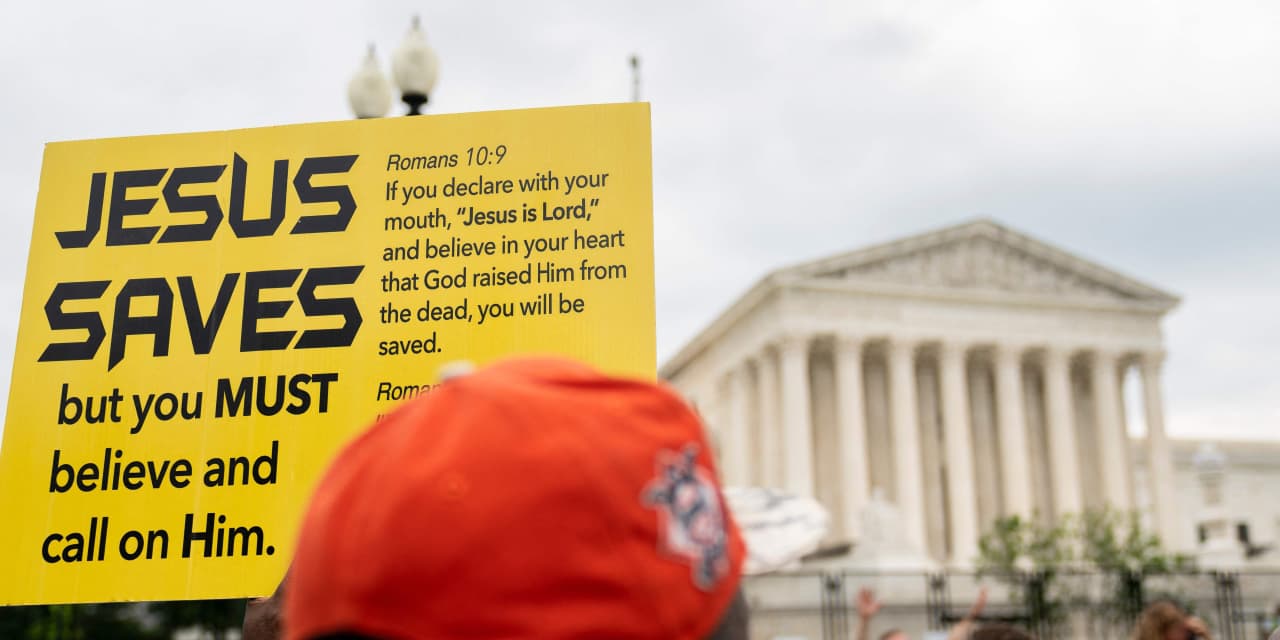

Do devout Christians have to work on Sundays? Will businesses have to make greater accommodations for devout Jewish or Muslim workers? This week the Supreme Court could, for the first time in almost 50 years, dramatically reshape federal rules that govern how employers must treat religious employees.

A ruling on a case called Groff v. DeJoy could come on Thursday. Plaintiff Gerald Groff is a former employee of the U.S. Postal Service who sued the service after being required to work on Sundays despite his religious Christian beliefs.

How the case came about

The roots of the dispute go back to a 2013 U.S. Postal Service agreement with Amazon

AMZN,

to deliver its packages to customers on Sundays.

Groff initially transferred to another post office branch that did not participate in the Amazon arrangement so he could continue to observe the Sabbath. But eventually, his new location also began to make Sunday deliveries.

The post office allowed Groff to swap shifts with co-workers to accommodate his observation, but because the location had only four employees, shift-swapping was difficult and Groff’s co-workers reportedly grew frustrated.

After Groff missed 24 Sunday shifts, the USPS took disciplinary action against him. Believing he would be fired, Groff resigned in 2019.

Groff then filed a religious-discrimination suit against the USPS based on Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

What does the Civil Rights Act say?

The act’s Title VII protects employees and job applicants from workplace discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

In 1972, Congress expanded religious protections for workers by amending the law to require companies to “reasonably accommodate” all religious practices by employees that can be observed without “undue hardship” on the business.

Five years later, in a case called Trans World Airlines v. Hardison, the Supreme Court further defined “undue hardship” for religious accommodations as a “de minimis” or bare-minimum cost. In other words, businesses could argue that almost any cost to them was a hardship, making it easier for them to deny religious accommodation for workers.

A decision in favor of Groff could overturn the de minimis standard for undue hardship set in 1977 and make it harder for businesses to deny religious accommodation.

How would an expansion of religious freedom affect the workplace?

It’s unclear. Opponents of Groff, like Americans United for the Separation of Church and State, argue that expanded religious protections could have negative effects on the workplace and harm morale among workers.

If employers are required to adjust schedules to accommodate an employee’s religious observation, critics say, other employees may get frustrated when they must fill in for their co-workers. Employers also might have to pay higher wages to incentivize other workers to take on undesirable shifts, for example.

Groups in favor of expanded protections, like the Muslim Public Affairs Council, contend new rules would benefit businesses by increasing employees’ work satisfaction and making them feel more committed to their jobs.

What might be the long-term implications of Groff v. DeJoy?

A decision in favor of Groff would make it more difficult for businesses to deny reasonable accommodation for employees’ religious beliefs.

The Groff case specifically focuses on work schedules, but it could also offer more protections for employees who wear hijabs, yarmulkes or other religious attire at work.

A decision in favor of Groff will give religious minorities a “fighting chance in court to prevail on their religious-discrimination claims” Joshua McDaniel, faculty director of Harvard Law School’s Religious Freedom Clinic, argued in an interview with the newsletter Harvard Law Today. This decision would protect individuals from having to decide between their faith and their work, he said.

Some groups opposed to Groff worry that a more expansive ruling could allow religious employees to opt out of serving LGBTQ+ patrons or providing care to women seeking abortions, to cite some examples.

It could open “the floodgates of discrimination against LGBTQ people, women, people seeking reproductive health care, religious minorities and other vulnerable communities,” Rachel Lasar, the president of Americans United for the Separation of Church and State, said in a statement.

Oral arguments at the Supreme Court were narrowly focused and did not touch on broader accommodations. But if Hardison is overturned, it could lead to a flurry of new cases that might force the court to adopt new and potentially controversial rules on religious protection.

How do observers expect the court to rule?

The Roberts court has been receptive to claims for more religious protection. In recent years, rulings have allowed employers to deny contraception coverage based on religious exception, required state funding for private schools to apply to religious institutions, and permitted a Catholic foster-care agency to deny services to same-sex couples.

The pattern suggests that the court could partially enhance religious protections, perhaps by altering the de minimis standard.