This post was originally published on this site

Even after a rough January for Wall Street, it might take the U.S. economy slipping into a recession before the S&P 500 index risks entering a bear market, according to Oxford Economics.

“Equities are flirting with correction territory. We think this drawdown may have a bit further to go as investors grapple with a more hawkish Fed and slowing earnings momentum,” wrote David Grosvenor, director of macro strategy at the economic research and analytics firm, in a note Monday.

“However, we do not think it is the beginnings of a new bear market and we remain modestly overweight on global equities over our tactical horizon, albeit with a relative underweight on the growth-heavy U.S. market.”

The rate- sensitive Nasdaq Composite Index

COMP,

already entered correction territory in mid-January, after closing at least 10% below its November record finish, while the small-capitalization Russell 2000 index

RUT,

last week slipped into a bear market, defined as a fall of at least 20% from a recent peak.

The S&P 500

SPX,

also spent several sessions in late January trading below its correction level of 4,316.905 intraday, but avoided closing below that key mark. The rally for stocks on Monday, with the S&P 500 powering 1.9% higher, put even further distance between it and correction terrain.

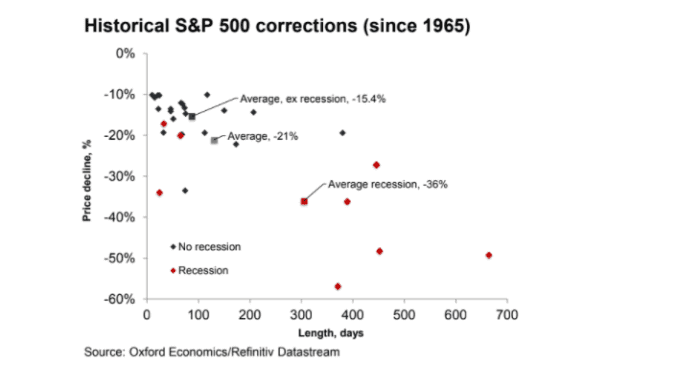

What’s more, when the economy isn’t in a recession, historical corrections for the S&P 500 have meant average declines of about 15.4% (see chart), with “very few resulting in bear markets,” according to Grosvenor.

S&P 500 rarely falls into a bear market outside of recessions

Oxford Economics

“Given that a recession appears unlikely at this time, with global growth forecast to remain above trend this year, we see this lower average as the more useful guide to the potential scale of the decline.”

Corporate balance sheets also appear to be in “a better condition than before the pandemic,” according to Grosvenor, who also noted big companies hold large cash buffers and have pushed out their debt maturities in the past two years of ultra low rates. All that makes defaults and widespread corporate distress less likely without “fairly aggressive” tightening of financial conditions or a “meaningful downturn.”

See: What to expect from markets in the next six weeks, before the Federal Reserve revamps its easy-money stance