This post was originally published on this site

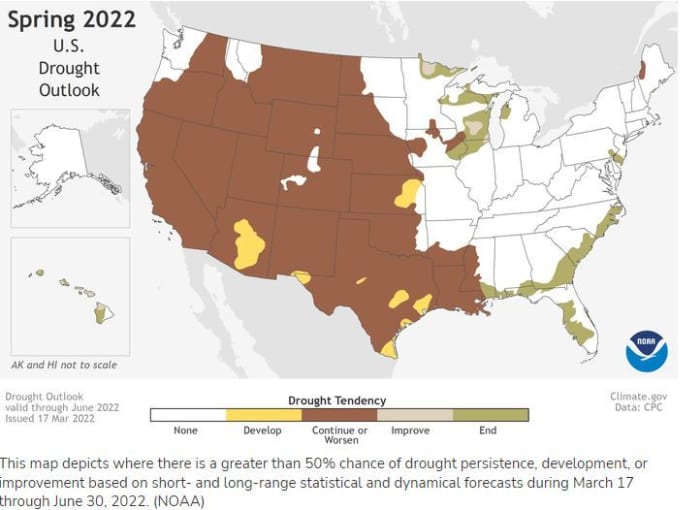

There’s little relief in sight for the multiyear megadrought that’s sapped Western U.S. reservoirs, intensified wildfires and helped drive up costs in California’s bread basket for the nation, forecasters say.

The region faces another spring and summer of dwindling water resources

PHO,

and rising temperatures, according to an outlook this week from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

From April to June, chances remain high that little rain or snow will fall from Northern California and Oregon across a wide swath of the Rocky Mountain states to Texas and the U.S. Gulf Coast, according to NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, which is part of the National Weather Service.

Special Report: Western Drought Watch

At the same time, warmer-than-normal temperatures will impact most of the contiguous U.S., except for parts of the Pacific Northwest.

Scientists say the U.S. West is broadly experiencing the worst megadrought in 1,200 years, made more intense by climate change.

“With nearly 60% of the continental U.S. experiencing minor to exceptional drought conditions, this is the largest drought coverage we’ve seen in the U.S. since 2013,” said Jon Gottschalck, chief operational prediction branch, at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

NOAA

The impact on California can’t be overly stressed. The state’s GDP in 2021 was $3.35 trillion, representing 14.6% of the total U.S. economy. If California were a country, it would be the 5th largest economy in the world, more productive than India and the United Kingdom.

Over-promised?

California produces over 25% of the nation’s food supply. Its ag sector is a nearly $50 billion industry, producing over 400 key commodities, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

California had nearly $20 billion in estimated annual agricultural sales put at risk by drought in recent years, as detailed in the Drought Aware app from Esri, which compiles layers of public data in one spot to show how conditions have changed in the U.S. over two decades and how much agricultural business may be at risk.

The last time the state faced a drought nearing this magnitude, such as in 2014, food economists said consumers could expect prices to rise about 3% directly related to water conditions. An inflationary post-pandemic recovery is also currently a factor.

But the experts predicted the state’s agriculture industry could feel residual impact for years. Already, severe drought last year caused the California ag sector to shrink by an estimated 8,745 jobs and shoulder $1.2 billion in direct costs as water cutbacks forced growers to fallow farmland and pump more groundwater from wells, according to research reported by the Los Angeles Times.

California water officials told state agencies on Friday to expect even less water from state supplies than the small amount they were promised to start the year, as major reservoirs remain well below their normal levels.

California’s water use went up in January despite calls for conservation, though Gov. Gavin Newsom has stopped short of mandatory cutbacks.

“The wiser we are with the use of water now means the more sustainable we are if the drought persists,” the state’s Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot said earlier this week. “Water is a precious resource, particularly in the American West, and we have to move away from clearly wasteful practices.”

Farming operations in the Central Valley have long turned to pumping more groundwater during droughts, and water levels have been dropping for decades. State lawmakers in 2014, another major drought period, passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. It established a framework for managing groundwater and required local agencies to develop plans to eliminate problems of chronic overpumping.

Yet the dry conditions that began in 2020 are demanding more conservation, as reservoirs such as Lake Oroville and Shasta Lake remain below historical levels and less water from melting snow is expected to trickle down the mountains this spring, an effect of climate change.

Current predictions estimate the state will see about 57% of the historical median runoff this April through July, Alan Haynes, hydrologist in charge for the California Nevada River Forecast Center of NOAA, told the Associated Press.

Some officials told the AP the state needs to plan for more droughts in the future by spending money to line canals to protect against water loss, improving groundwater basins and providing even more financial incentives for people to make their properties more drought friendly. The state’s plans to expand water storage got a boost Thursday when the federal government indicated it will loan $2.2 billion to help build a new reservoir.

But critics of California’s water policy say the larger problem is that the state promises more water each year than it has to give. That’s led to a continued diminishment of supply in federally and state run reservoirs, said Doug Obegi, an attorney focused on water for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“We basically have a system that is all but bankrupt because we promised so much more water than can actually be delivered,” he told the Associated Press.

Great Lakes: From drought to flood

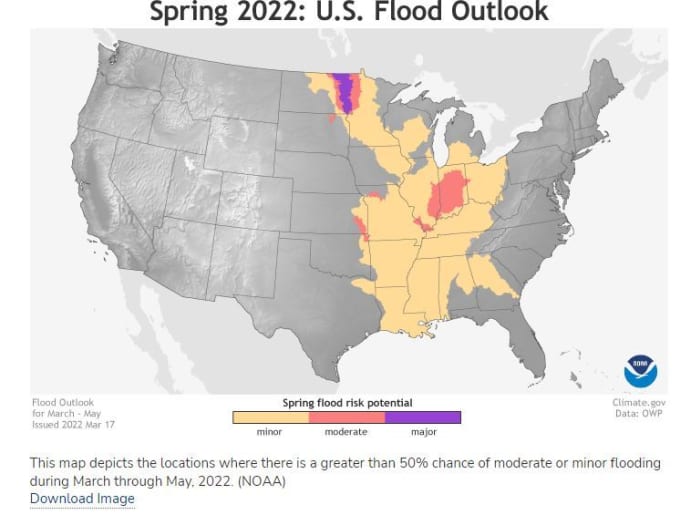

Above-average precipitation is most likely in portions of the Great Lakes, Ohio Valley, mid-Atlantic and the west coast of Alaska, NOAA said.

NOAA

There is a minor-to-moderate flood risk throughout much of the eastern half of the continental U.S., including the Southeast, Tennessee Valley, lower Mississippi Valley, Ohio Valley and portions of the Great Lakes, upper Mississippi Valley and middle Mississippi Valley, the forecast shows.

“Due to late fall and winter precipitation, which saturated soils and increased streamflows, major flood risk potential is expected for the Red River of the North in North Dakota and moderate flood potential for the James River in South Dakota,” said Ed Clark, director, NOAA’s National Water Center.

Spring snowmelt in the western U.S. is unlikely to cause flooding.

The Associated Press contributed.