This post was originally published on this site

Should you FIRE the 4% spending rule in retirement?

My play on words refers to the “Financial Independence, Retire Early” movement, as it applies to the standard retirement spending rule that many financial planners have traditionally recommended.

New research has analyzed whether changes need to be made to that rule if you’re planning for a 50-year retirement—which is the avowed goal of some followers of the FIRE movement.

Read: Forget retirement, focus on financial independence

That’s a significant increase in retirement length from the 30-year period that was presumed by the original research that led to the development of the 4% rule. Do adjustments need to be made to accommodate that longer horizon?

The new research that attempts an answer to this question comes from mutual-fund giant Vanguard. Entitled “Fueling the FIRE movement: Updating the 4% rule for early retirees,” the firm’s study finds that, as that horizon lengthens, the odds of running out of money increase dramatically.

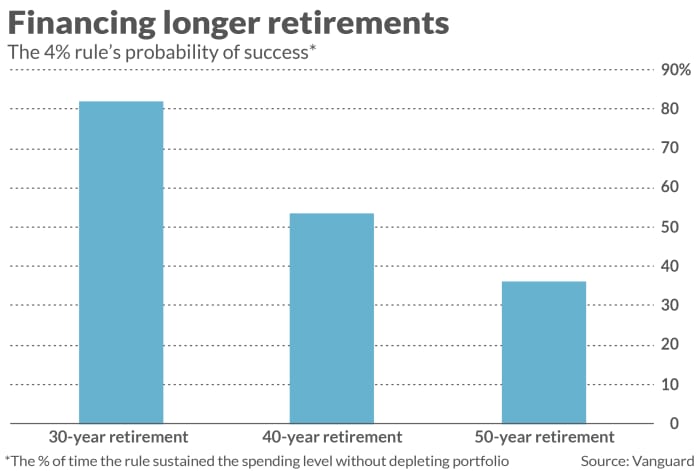

The accompanying chart shows by how much. At a 30-year horizon, there is an 18% chance of running out of money. While low, this is higher than found in the original research, primarily because Vanguard assumed that stocks’ and bonds’ returns in the future would be lower than their historical averages. That 18% failure rate nevertheless provides a baseline to measure the impact of extending the retirement horizon.

At the 40-year horizon, while making no other changes to the underlying assumptions, the failure rate rises to 46%. And at the 50-year horizon, it is 64%. In essence, Vanguard found that if you retire at age 40 and expect to live 50 years, there’s a two-out-of-three chance that you will run out of money when using the 4% rule to determine how much you withdraw each year to live on.

You should not be particularly surprised by Vanguard’s findings that risk of failure grows along with investment horizon. I discussed this phenomenon a couple of months ago, you may recall, when I reported on research conducted by Zvi Bodie, who for 43 years was a finance professor at Boston University. Specifically, he calculated what an insurance company would need to charge for a hypothetical policy that paid off if the stock market, at the end of the policy period, was lower than at the beginning. Bodie found that the premium the insurance company would have to charge for this policy increases as the length of the policy lengthens.

How to respond

The only solution to running out of money is to spend less, of course. But there are strategies for spreading that pain out over longer periods and, hopefully, making it more tolerable. That requires adjusting the amount you withdraw from your retirement portfolio each year, in contrast to the 4% rule’s assumption that you withdraw the same (inflation-adjusted) amount each and every year.

Researchers over the last several years have proposed any of a number of these so-called “dynamic” spending rules. The general idea is that you withdraw more in years in which the markets have performed well, and less in years in which the markets have performed poorly. (I devoted a Retirement Weekly column two years ago to an early academic study of dynamic spending rules.)

In its recent study, Vanguard analyzed several different dynamic spending rules. To illustrate what they found with one plausible rule, consider a hypothetical $1 million portfolio at retirement. In the case of the original 4% rule, that would translate into a withdrawal of an inflation-adjusted $40,000 in each retirement year—until you ran out of money, in which you would have nothing to live on. For the dynamic spending rule that Vanguard analyzed, the worst case year (worse than 95% of all years) led to spending an inflation-adjusted $24,709—and you never would run out of money.

There’s no doubt that this smaller sum represents a big reduction from $40,000. But it’s a whole lot better than zero.

But if that reduction is intolerable, you will need to amass a larger portfolio if you plan to retire at age 40, or work longer before you retire.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.