This post was originally published on this site

Last month the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released its most recent U.S. life expectancy estimates, and sadly, the report found that, once again, Americans’ average number of years remaining have fallen. As reported recently, life expectancy at birth is now 76.4 years (as of 2021), down from 77 a year earlier. This is a drop of approximately 7 months over a one-year period, which takes life expectancy back almost a quarter-century to 1996.

This decline is certainly dreadful news. Yet, as financial educators and researchers, we are concerned that the way in which such information is presented to the public will be widely misinterpreted. Even worse, we fear that many Americans will read such reports and take the wrong actions, based on a misunderstanding of how mortality information should be incorporated in retirement planning and saving. Instead of panicking, we should take on a risk management mind-set.

Read: Want a happier, more fulfilling retirement? Try this Japanese concept.

Twin crises in retirement decision making

Our research highlights two emerging crises for Americans making financial decisions about later life: their financial illiteracy, and the difficulty they have planning for retirement.

For instance, fewer than half of adults can correctly answer three basic financial questions about interest rates, inflation, and risk diversification, and only about 40% of Americans say they ever even tried to figure out how much to save for retirement. Moreover, two-thirds of people surveyed report they have less than one month’s income saved for emergencies, and one third has no retirement savings account.

So just imagine what the financially illiterate and under-saving public will think on seeing these new life expectancy estimates. Many may tell themselves: “Well, if I’m only going to live to age 76, then why should I bother saving anything for retirement?” Or, even worse, they could extrapolate that drop of 7 months and conclude that, in about 130 years, human life expectancy will be zero!

Read: What would you regret if your retirement lasted only one year? Don’t delay joy in retirement.

What can be done?

Those who understand statistics and mathematics might scoff at such erroneous conclusions for a couple of reasons. For one, linear extrapolations produce absurd results, as noted above. For another, the CDC life expectancy report refers to a period rather than a cohort measure. The period life table charts deaths in a population during a specific time period, while the cohort table includes predictions of anticipated changes in future survival rates for people alive today.

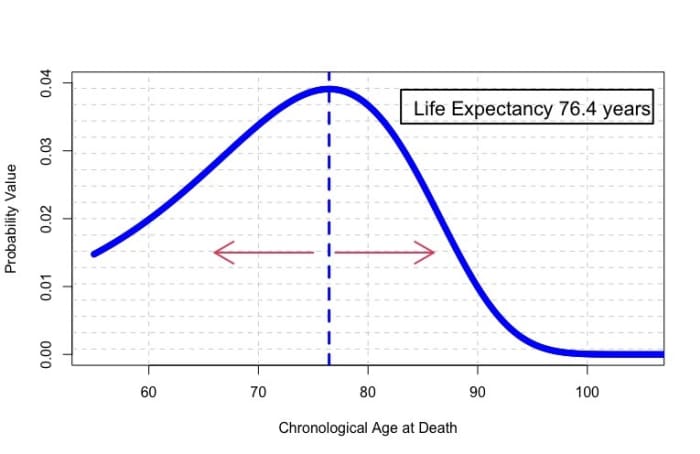

So, you might ask, how can we help average Americans understand what the new data mean? We propose that it’s high time the CDC, and by extension the financial media, begin reporting not only average American lifespan (the 76.4 years noted above), but also the standard deviation or dispersion in years of mortality around this average. This is because people tend to erroneously interpret life expectancy numbers as how long they will live, but there is actually quite a wide range or dispersion around the average.

Read: Secure 2.0: How the new retirement law may affect you and your savings

In the case of older Americans, this range is easily on the order of 10 years (a standard deviation around the average), which means that newborns can be expected to live anywhere from 60 to 90 years. People wanting to be more confident about how long their lives will last, so they can better prepare for retirement, will need to add another standard deviation or decade of life — taking them to age 100. This approach provides a better estimate of longevity risk, or the chance that people will outlive their money in old age. The following figure provides an idealized view of longevity risk, where life expectancy is just a midpoint.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Interestingly, the evidence suggests that retirees greatly underestimate their longevity risk, providing policy makers with a rationale to support defined benefit pensions and social security. This also explains why the U.S. Congress recently passed legislation enshrining the importance of income annuities to better protect people against longevity risk. In fact, the dispersion displayed in the figure is precisely why lifetime income annuities are so important in a well-crafted retirement plan.

Annuities help insure those who experience longer than average lifetimes by “pooling” longevity risk with those who live shorter lives. Alas, focusing only on the average assumes away one of the largest challenges in retirement: the uncertainty of it all.

Risk management key to avoid disaster

Our plea, therefore, is twofold.

First, the CDC and other news media should begin reporting not just average life expectancy numbers, but also the range or dispersion around this concept, to better guide the millions of Americans who suffer from low financial literacy and poor retirement preparedness.

Second, Americans themselves should stop thinking, budgeting for, and planning for retirement as if it was a fixed and known length of time, and instead adopt a risk management mind-set.

Olivia S. Mitchell is the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans Professor, and Professor of Insurance/Risk Management and Business Economics/Public Policy, at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Moshe A. Milevsky is a Professor of Finance and member of the Graduate Faculty of Mathematics and Statistics, at York University in Toronto.