This post was originally published on this site

The annual Social Security Trustees Report, finally been published four months after its legally required date, projects that Social Security’s trust fund will be exhausted in early 2034, a year early than was projected in last year’s report. Social Security’s long-term funding shortfall grew by 10%, with the plan’s unfunded obligations totaling $19.8 trillion.

So how worried should you be? I’ll turn 65 in 2033, so you’d think I’d be really worried. And yet I’m not, or at least not for the reasons you would think.

Read: Social Security’s doomsday is now a year earlier — should you be worried?

Social Security’s insolvency isn’t a big threat to Americans’ retirement security. But Social Security’s rising costs do threaten to squeeze out other government priorities, such as health, education and infrastructure.

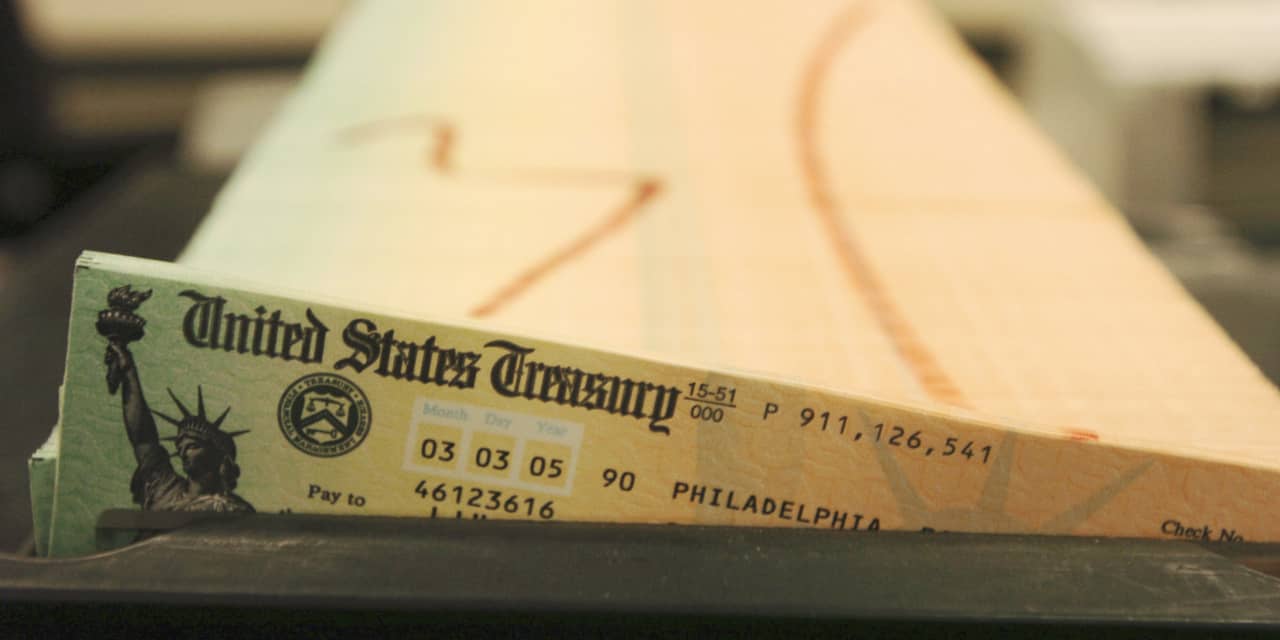

When I served at the Social Security Administration during the George W. Bush administration, SSA’s lawyers confirmed that Social Security can’t write checks unless it has money in the bank to pay them. Today, Social Security is relying on the trust fund to pay full benefits, since the cost of paying benefits rose above the taxes collected by the program in 2009. But in early 2034 the trust fund’s assets – consisting of past payroll tax surpluses that were invested in special-issue Treasury bonds – will run dry. Payroll tax revenues alone would be enough to pay only 78% of promised benefits.

Now if that were to happen, it truly would precipitate a “retirement crisis.” And yet a sudden, across-the-board Social Security benefit cut is almost impossible to conceive. And I say that as someone who for years has argued that the best way to solve Social Security’s funding shortfall is via benefit cuts, albeit not sudden and across-the-board ones.

But — and I can say this with certainty — that’s not what Congress will do.

For instance, the Social Security Disability Insurance program’s trust fund was projected to run out in 2016. Did Congress allow benefits to be cut, or even to enact any reforms to the troubled disability program? No. It instead transferred funds from Social Security’s retirement program to keep benefits flowing. No Disability Insurance beneficiary saw a penny of benefit cuts.

Then just this past year, Congress passed an $80 billion-plus bailout of underfunded multiemployer pension plans, which are jointly run by labor unions and employers across industries such as trucking, mining and supermarkets. The federal government had no legal or financial obligation to bail out these poorly managed plans. And yet Congress did so, because these workers and retirees were a sympathetic group that, as union members, carried a great deal of political clout.

So if Congress wouldn’t cut benefits for the disabled or for union members, what is the chance Congress will allow large, across-the-board benefit cuts for Americans who paid into Social Security for decades? Not very large, and I’m willing to wager my own retirement security on that.

Congress could keep channeling general tax revenues to Social Security, as it currently does to repay the trust fund’s special Treasury bonds. Or it could raise taxes. Or Congress would simply borrow. But the risk of substantial benefit cuts, especially for low-income retirees who rely on Social Security the most, is remote.

Does this mean Social Security’s insolvency is nothing to worry about? No. It’s a big problem, just not necessarily one for retirees. Social Security has long been the largest federal spending program. And over the past 20 years, Social Security’s costs have risen by 30% relative to the size of the economy, with another 12% increase relative to GDP projected between now and 2033.

Some of that increase is simply due to demographics – more retirees and fewer workers to support them. But benefit levels have increased as well; SSA data shows the average new retiree receives a monthly benefit that’s 37% higher after inflation than a similar new retiree 20 years ago, generated by the growth of worker’s wages and delayed claiming of retirement benefits.

Future benefits will be even higher, and much of that increase will flow to middle and high-income retirees who aren’t in pressing need. That’s a lot of extra money for Social Security that can’t be used for other things, like health, education or infrastructure. As long as the trust fund lasts, Social Security has a legal claim on those extra dollars.

But the trust fund will run out precisely because, for decades, Americans via their elected officials have chosen not to pay the extra taxes needed to keep the system permanently solvent. So it’s not illegitimate for Congress to ask whether additional dollars should go toward Social Security benefits or to other government priorities.

Yes, Congress needs to devise a plan to avoid Social Security’s insolvency. But that’s the easy part. What Congress really needs to do is decide how much of our future resources should flow to providing higher Social Security benefits to retirees whose incomes already are at record levels. That’s harder to do.

Andrew G. Biggs is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and former principal deputy commissioner of the Social Security Administration during the George W. Bush administration. Follow him on Twitter @biggsag.

Now read: If Social Security falls into crisis, voters will have no one to blame but themselves