This post was originally published on this site

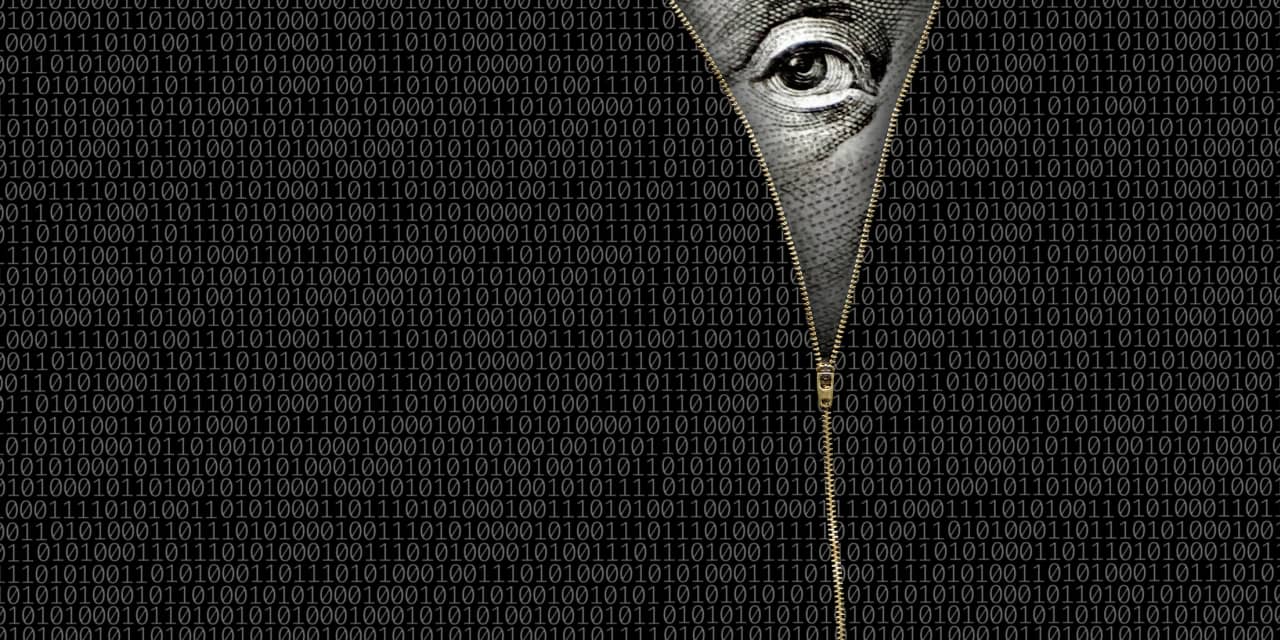

Fearful of being drawn into a war in Ukraine, the West is depending on economic consequences to put pressure on Vladimir Putin’s regime. To a large extent, these efforts depend on transparency: the more we know about who is doing what in the global financial system, the easier it is to respond quickly when we want to do so.

But the U.S. has made that task harder by Washington’s historical indulgence toward corporate secrecy. America’s lax regulation of corporate entities such as LLCs has given haven to money launderers, corrupt foreign officials and shadowy international business operatives intent on influencing our political system.

Ironically, much of this wrongdoing has been fostered by President Joe Biden’s home state of Delaware, the overwhelming destination of choice for out-of-state business registrations. Delaware has more registered companies (1.6 million) than residents (fewer than one million), and it is easier to set up a business there than to get a library card. No ID is required. No owners need be identified.

This has left U.S. officials with a shocking lack of insight into the business activities that take place within their jurisdiction and under the protection of their laws. Earlier this year I asked the Delaware Secretary of State’s office what proportion of companies registered in the state were foreign-owned. They responded that they do not know, and that there is no way of knowing.

To be fair, states other than Delaware have also profited from a lack of transparency. But Biden’s backyard has practiced corporate secrecy on an industrial scale. The various streams of revenue that flow from the incorporations industry account for around 40% of Delaware’s state budget, and the sector is one of its biggest employers.

One example of foreign dark money flowing through Delaware came during the last U.S. presidential election cycle, when Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, two Soviet-born Americans, were indicted by federal authorities for allegedly using a Delaware LLC to funnel millions of dollars of political donations from Russia to U.S. political campaigns.

Parnas and Furman were dramatically intercepted together at Dulles International Airport in October 2019, moments away from fleeing the country. The two were in the process of boarding a Lufthansa flight to Frankfurt amid a gaggle of first-class passengers before plainclothes officers apprehended them. Both men had one-way tickets, en route to Vienna and perhaps various points east.

Each had been closely associated with Rudy Giuliani and with the Trump administration’s attempts to gather damaging information in Ukraine about Candidate Biden—attempts that would lead directly to Trump’s impeachment by the House of Representatives in December 2019. (The Senate voted not to convict.)

“ The various streams of revenue that flow from the incorporations industry account for around 40% of Delaware’s state budget. ”

Parnas was convicted last year, and Fruman this year, on campaign finance charges. They had used Global Energy Producers, an LLC they registered in Delaware in April 2018, as a front for funneling a $325,000 donation to America First Action, a pro-Trump super PAC.

In a twist that betrayed unbridled chutzpah, Parnas was also found to control several other Delaware entities, including two named Fraud Guarantee LLC and Fraud Guarantee Holdings LLC.

Delaware likes to stress that such examples are the exception and that the overwhelming majority of business owners are above board. That is undoubtedly true: it would be absurd to suggest that most of the entities registered in Delaware are designed with nefarious ends in mind.

But without ownership information, it has always been impossible to know the scale of the problem. It would not be unfair to assume, given the lack of information traditionally available to law enforcement, that not all criminal shell companies have always been exposed and shut down. And while it’s not clear whether the known cases were the tip of an iceberg or something bigger, it’s at least likely that they did not represent the entirety of the problem.

Congress passed legislation last year that should in theory end the flow of foreign money into U.S. politics. The Corporate Transparency Act, whose details are still being ironed out, will require companies registered in the U.S. to identify their owners to the federal government, even if the “no questions asked” policy will still apply at the moment when the businesses are created, in Delaware or elsewhere.

But the registry of corporate owners will be visible only to government agencies, and the political donations of U.S.-based corporations (including U.S. subsidiaries of foreign parent companies) and wealthy individuals that aren’t out-and-out illegal will remain in the dark.

The U.S. public deserves to know who is behind the companies set up on its soil. The European Union, the U.K., Canada, the British Virgin Islands and the United Arab Emirates have committed themselves to public access to their corporate registries. So has Ukraine. The U.S. should join them.

Hal Weitzman is the executive director for intellectual capital at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, and editor-in-chief of Chicago Booth Review and the author of “What’s the Matter with Delaware?: How the First State Has Favored the Rich, Powerful, and Criminal—and How It Costs Us All“.