This post was originally published on this site

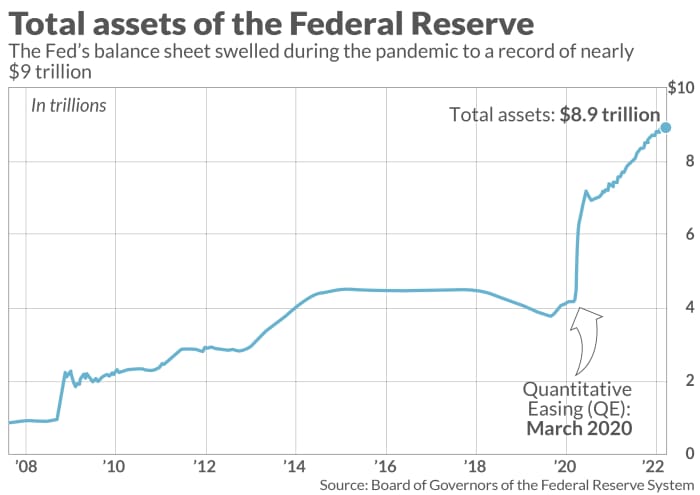

As the Federal Reserve gears up to shrink its near $9 trillion balance sheet to help cool U.S. inflation running at 40-year highs, tricky questions can emerge about what happens next to the money in the system.

Does some of the money go out of existence, effectively shrinking the money supply? Or does it go somewhere else?

MarketWatch asked a handful of industry experts to help explain the financial plumbing that connects one the world’s most powerful economic institutions to financial markets, the economy and the government’s purse.

Here’s an overview of what happens when the Fed stops creating “money out of thin air” as Luke Tilley, chief economist at Wilmington Trust, described it in an interview with MarketWatch, and starts to “reduce the amount of money in the economy.”

Where money comes from

To help stabilize markets during the pandemic, back in 2020 the Fed started buying Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities at a $120 billion monthly pace, through BofA Securities

BAC,

Citigroup Global Markets

C,

J.P. Morgan Securities

JPM,

and other primary dealers, or the 24 large banks and brokers now authorized to deal directly with the central bank.

As the central bank’s holdings increased (see chart), that infused financial markets with liquidity and confidence to keep credit flowing. It also helped usher in a speedy economy recovery from early pandemic shocks. More recently, it also has been blamed for letting exuberance run too high in some asset markets, which could fizzle and result in painful losses.

MarketWatch illustration

As Wilmington Trust’s Tilley, a former Fed staffer, put it, the Fed buys securities and adds money to dealer accounts, with the aim of increasing money in the economy.

A way to track the “oceans of cash” piling up at banks under easy-money policies, is through banking reserves (see chart below), or the amount sitting at the Federal Reserve, earning 0.15%.

Importantly, banking reserves are part of the monetary base, but only add to the money supply when they are deployed and start circulating in the economy, Tilley said.

In an ideal scenario, some reserves flow out of banks to businesses and households in the form of loans to spur economic growth, but without loading up too much debt that could backfire in the form of defaults.

Another way to track cash looking for a home is to note the deluge of funds parked overnight at the Fed’s reverse repo facility, which a year ago sat nearly unused but increased lately to roughly $1.5 trillion daily.

“That’s about a $5.5 trillion pile up of cash,” said Mark Cabana, head of U.S. rates strategy at BofA Global.

The Fed Chairman Jerome Powell now has the difficult task of tightening financial conditions to help tackle inflation pegged at 7.5% in January, or well above its 2% annual target, while high fuel, food and housing costs threatening to spark a slowdown or recession.

Unsettled markets

Market jitters around the Fed’s next moves already can be found this year in tumbling stocks

SPX,

DJIA,

but also in the U.S. high-yield

HYG,

JNK,

or “junk-bond” market, where debt issuance has been largely on pause since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led oil and commodity prices to soar.

High-yield bond issuance has been about 70% lower so far in 2022 from a year ago, said Bill Zox, high-yield portfolio manager at Brandywine Global Investment Management, in a phone call.

“Look, there is no question the new-issue market could shut down,” Zox said of deeper turmoil that could be unleashed as the Fed looks to raise rates for the first time since 2018 and shed assets. “That isn’t my base-cased right now, but it is a lot more of a possibility today than it was a month ago.”

Read: Four things to watch at conclusion of Fed meeting on Wednesday

Where money goes

The Fed remits profits accumulated on its holdings to the U.S. Treasury Department once a year, which in 2020 equaled nearly $90 billion to help cover the government’s bills.

As the Fed looks to reduce the amount of money in the economy it can do it several ways, including passively letting maturing bonds pay off.

BofA Global estimates that about $1 trillion worth of Fed-held bonds will mature this year, with roughly the same amount due in 2023, which would take a sizable bite out of its balance sheet.

“They bought bonds with the idea that in the next two-to-four years, a lot would be maturing, so they wouldn’t have to sell anything,” said Jim Vogel, interest-rate strategist at FHN Financial, by phone.

Sounds easy enough, but Cabana, also a former Fed staffer, argues that passive balance sheet reduction still requires the Treasury to issue more debt to the public in order to top up the Fed’s maturing holdings, which “destroys” banking reserves, demand for the Fed’s reverse repo program, and shrinks the amount of money at the ready.

And if the Fed no longer serves as a key buyer of its debt, others would need to step up as the Treasury lays out its expected quarterly funding needs in the months ahead.

“The big risk here is that there is too much debt outstanding for the market to easily take down,” Cabana said. “The question is what’s the impact on financial conditions, and risk appetite.”

A more measured approach might be for the Fed to reinvest some proceeds from maturing bonds to buy more, thereby regulating the pace of its balance sheet runoff, as it did after the 2008 financial crisis. Unlike earlier in the pandemic, however, the Fed now would be buying bonds directly from the Treasury, bypassing primary dealers.

A third, perhaps more disruptive way would be for the Fed to sell bonds on its books directly into the marketplace.

MarketWatch illustration

“If it sells bonds, the market would have to buy them,” Vogel said. “The the simplest terms, the Fed stops throwing stones into the pond. But even after it stops, there are a whole series of ripples.”