This post was originally published on this site

The clock is ticking down to what’s expected to be a default by the Russian government after sweeping sanctions impaired its ability last week to make payments in dollars on foreign debt.

If so, it would mark the country’s first default since a 1998 crisis that resulted in the collapse of hedge fund Long Term Capital Management and necessitated a bailout by Wall Street banks — and it would be Russia’s first default on foreign debt since the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, economists said.

What happened

Russia’s finance ministry last week said it attempted to make around $649 million in coupon and principal payments on a pair of dollar-denominated bonds, but that sanctions prevented the payments from being accepted. Russia instead made payment in rubles, which isn’t allowed under the terms of the bond.

That kicked off a 30-day grace period, which ends May 4, according to The Wall Street Journal, for Russia’s government to make payment in dollars or to be deemed in default.

S&P Global Ratings late Friday downgraded Russia to “selective default” after Russia arranged to make the foreign bond payments in rubles on April 4. The ratings firm said it didn’t expect Russia to be able to convert the rubles into dollars within the 30-day grace period allowed.

What’s coming

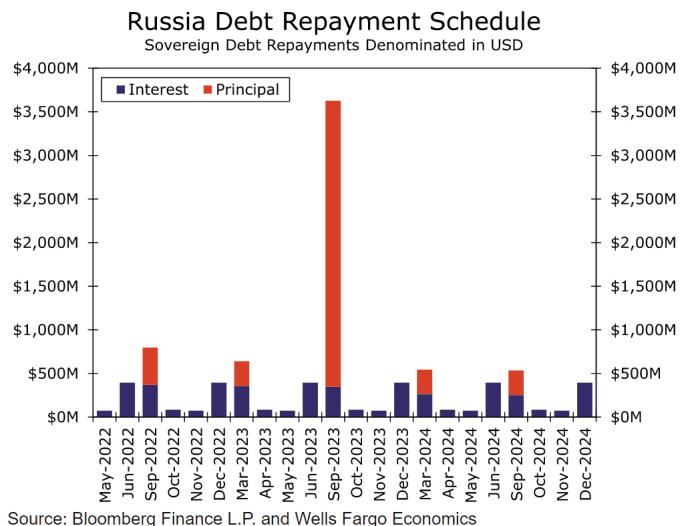

Russia faces a steady stream of dollar-denominated payment deadlines in coming months, and while the payments aren’t particularly large, Moscow will face the same obstacles that could see additional bonds enter the grace period and then potentially be defaulted on, wrote economists at Wells Fargo, in a note.

They noted Russia faces $70 million of interest payments in May and nearly $400 million of coupon payments in June, while September obligations are more burdensome at around $800 million, including around $370 million of interest payments and the payoff of a sinkable bond worth around $425 million (see chart below).

Wells Fargo Economics

Investor reaction

The prospect of a Russian default after waves of sanctions by the U.S. and its allies against Moscow following the Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine is hardly a surprise.

“In our view, a default by Russia on its foreign debt is the inevitable consequence of financial sanctions, and in fact the goal of those sanctions,” said Carl Weinberg, chief economist at High Frequency Economics, in a note.

And while Russia’s government “seems willing to do whatever it can to avoid it happening, [a default] now seems to be priced in with a high probability,” said Joseph Marlow, an economist at Capital Economics, in a Friday note.

Global and U.S. investors have appeared to take the prospect of default largely in stride. U.S. Treasurys, which typically serve as havens during periods of geopolitical uncertainty or financial turmoil have sold off sharply after a brief flight to safety after the invasion.

Major U.S. stock indexes rallied back from early March lows, though the S&P 500

SPX,

Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

and Nasdaq Composite

COMP,

fell last week. The decline was widely attributed to worries over the Federal Reserve’s plans to tighten monetary policy rather than default fears.

Contagion risks

A Russian default would be relatively small, and financial authorities have played down the risks of ripple effects from a default on the financial system. International Monetary Fund Managing Director in March put total bank exposure to Russia at $120 billion — a figure she described as not negligible, “but definitely not systemically relevant.”

But what about other emerging markets?

After all, past sovereign defaults saw crises “ripple through Latin America in the 1980s, Asia in the 1990s and Central Eastern Europe (CEE) in the 2000s; and there have been other examples of contagion such as after the Russian ruble crisis in 1998,” wrote David Rees, senior emerging markets economist at Schroders, in a post last week.

But Rees said it appears unlikely a default by Russia would spark a wave of other credit events. Any default “would be due to sanctions preventing it from making payments, rather than economic problems.”

“And it is not the case that other EM have built up external vulnerabilities in recent years like those that preceded past regional crises,” he wrote. “Indeed, most EM have been fairly resilient in recent months as solid external positions and proactive interest rate hikes have provided insulation to global events.”

So nothing to worry about then?

Never say never, economists and market watchers warn. As Capital Economics warned last month, there’s the possibility that underneath the aggregate numbers, a systemically important institution is heavily exposed to Russian sovereign debt and is potentially capable of sending tremors through the financial system.

And a government default could be followed by corporates, the firm warned.

—The Associated Press contributed to this article.