This post was originally published on this site

It could take six more years for the Federal Reserve to shrink its mortgage bondholdings to less than $1 trillion, according to a new Goldman Sachs estimate.

The Fed’s balance sheet already has fallen to about $8 trillion from a near $9 trillion peak last year. But progress has been slow in shedding its $2.5 trillion in mortgage-bond holdings, an enduring vestige of its pandemic-era policies.

A big reason for that has been climbing U.S. mortgage rates, now north of 7%, with the Fed’s rate hikes putting refinancing and sales activity largely on ice.

The Fed last week suggested its policy rate could stay above 5% for longer than an earlier forecast, darkening the housing-market outlook and fueling worries that mortgage rates could reach 8%, instead of providing the relief many on Wall Street had been anticipating.

“Although many are locked into fixed rate mortgages, conditions for new buyers are strained,” Emin Hajiyev, senior economist at Insight Investment, wrote in emailed commentary.

As 30-year mortgage rates skyrocketed from a 2.7% pandemic low, home affordability sank to its lowest level since at least 1989, according to Hajiyev’s estimates. “For the first time since 2006, the median income does not qualify for the median property for sale.”

See: Interest rates will stay high ‘well into next year,’ Fed’s Goolsbee says

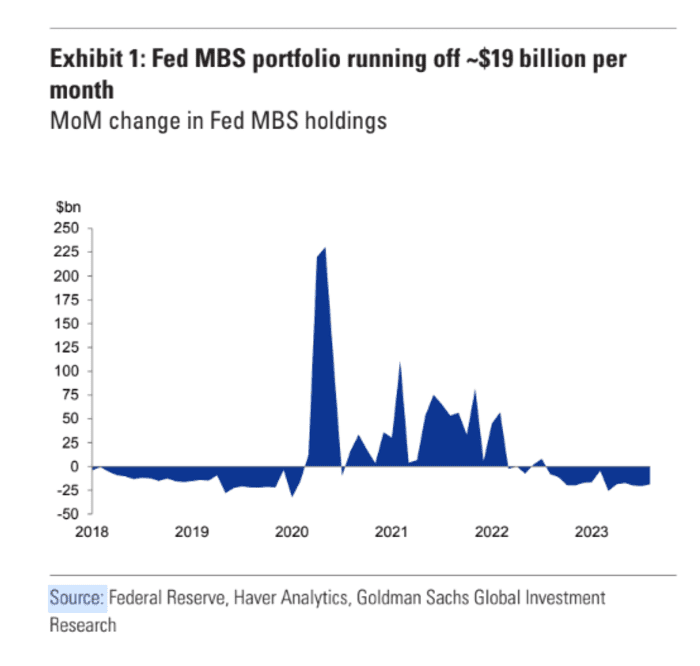

Goldman breaks down how the Fed’s footprint grew in the roughly $12 trillion agency mortgage-bond market since 2018, including its big uptick in purchases during the COVID crisis.

Fed’s mortgage-bond holdings are slowly shrinking each month, but falling below caps set last year. Higher rates for longer won’t help speed things up.

Federal Reserve, Haver Analytics, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

The Goldman chart also shows the Fed’s slow progress on unwinding its holdings. Mortgage-bond runoff this year has been far below the Fed’s $35 billion monthly caps, recently clocking in at about $19 billion. The Fed isn’t selling bonds to cut the size of its balance sheet, but letting its holdings mature.

The caps on runoff were designed to prevent shocks in financial markets as the Fed wrestles inflation down to its 2% yearly target through higher rates and by unwinding its pandemic bond purchases.

“With this ‘higher for longer’ backdrop we shift our focus to the Fed’s MBS portfolio which is now running off at ~$19 billion per month currently,” Goldman credit analysts led by Roger Ashworth, wrote in a weekly client note.

“MBS” is shorthand for mortgage-backed securities or mortgage bonds. The Goldman team thinks rate cuts in 2025 could boost the monthly MBS runoff to around $25 billion a month, but expect it to take until mid-2029 for the Fed’s mortgage-bond holdings to fall below $1 trillion.

The Fed said on Wednesday said it would hold rates steady but continue reducing its securities holdings.

The problem is mortgage bonds are highly sensitive to the Fed’s policy rate. Goldman analysts pegged the Fed’s mortgage bond portfolio at about a 3.2% weighted average coupon, a proxy for interest rates, making a $35 billion a month paydowns soon “seem very unlikely.”

Mortgages are priced at a premium to the risk-free Treasury rate. The benchmark 10-year Treasury yield’s BX:TMUBMUSD10Y sharp recent climb has it touching 4.51% on Monday, the highest since 2007.

Stocks were mixed Monday, with the S&P 500

SPX

and Nasdaq Composite

COMP

higher after posting their biggest weekly drops since the March banking crisis. The Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA

was near unchanged, as it also erased a modest early loss.

Read next: 10-year Treasury yield can keep climbing from 16-year highs, says world’s largest asset manager