This post was originally published on this site

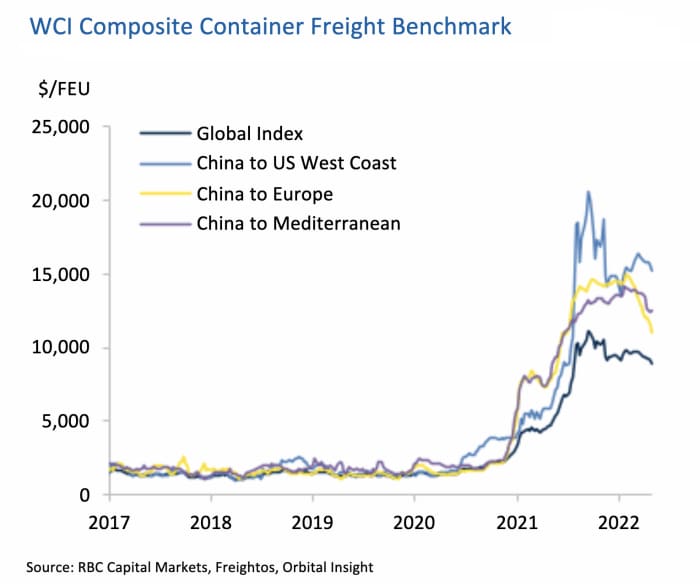

The lifelines of global trade are becoming more expensive, with port congestion worsening and turning widespread world-wide.

That’s according to a report released Tuesday by Michael Tran and Jack Evans at RBC Capital Markets, who use alternative data and geospatial intelligence to track 22 of the world’s largest and most influential ports. It points out that one-fifth of the global container fleet is currently stuck in congestion at various ports, and less than 40% of ships are arriving on time. Meanwhile, freight prices are still elevated, while marine fuel prices and insurance costs are soaring.

The report outlines a multitude of forces that are likely to translate into even-higher costs for consumers, already grappling with U.S. inflation at a four-decade high.

Widespread expectations that inflation may have already peaked, as suggested by some signs in the last consumer-price index report, may be “wishful thinking,” according to Ben Emons, managing director of global macro strategy at Medley Global Advisors, who has been tracking the flow of goods.

If anything, forces outside of the Federal Reserve’s control are growing, just as policy makers are getting ready to deliver their first 50 basis point rate hike in almost 22 years on Wednesday. And “there’s no way rate hikes will bring container ships back from Shanghai any quicker to L.A.,” Emons said by phone.

Read: Traders and investors may have bitten on a ‘head fake’ from a single soft U.S. inflation number

“We still haven’t seen the full ripple effect of supply chain issues that are now going global because of China’s COVID situation and Russia’s war on Ukraine,” Tran, RBC’s head of digital intelligence strategy, told MarketWatch by phone. “There are very few levers you can pull when you look at the ripple effects. We almost need to let it run its course.

“The lifelines to global trade are definitely becoming more expensive, and will definitely trickle down to the end user,” Tran said.

One implication of RBC’s findings is that financial markets could eventually come around to the view that the Fed and global central banks are helpless in fighting inflation, even while they hike rates. In such a scenario — which Emons describes as “outside of consensus, but within the realm of tail-risk possibilities” — the first sign of markets losing faith in the Fed would be a deeply negative yield curve — with the 2-year rate

TMUBMUSD02Y,

trading close to 4% and the 10-year rate

TMUBMUSD10Y,

around 3%, he says.

Equity prices would continue to fall and the U.S. dollar would turn “super strong with a total gain of 25% versus last year against other major currencies,” Emons said.

Key Words: ‘You don’t want to own bonds and stocks’ in this environment: Paul Tudor Jones

The dollar would benefit from its status as the world’s primary reserve currency in a scenario in which global central banks are unable to contain inflation, and a stronger greenback would eventually negatively impact commodity prices — pushing down the prices of everything from metals to agricultural products, he said. In a nutshell, U.S. markets would begin behaving more like an emerging market such as Turkey, which is grappling with a combined financial and economic crisis amid soaring inflation and a plunging lira.

Last year’s supply-chain woes, which Tran and Evans referred to as “Supply Chain Bottlenecks 1.0,” were largely a function of record consumer demand for goods. This year’s 2.0 version is exacerbated by China’s battle with COVID and Russia’s war on Ukraine. Inefficient operations at major ports also continue to wreak havoc, they said.

Congestion at the U.S.’s largest ports in Los Angeles and Long Beach ought to be improving, given a slowing line of ships transporting across the Pacific as China grapples with COVID. But that hasn’t happened, Tran and Evans said.

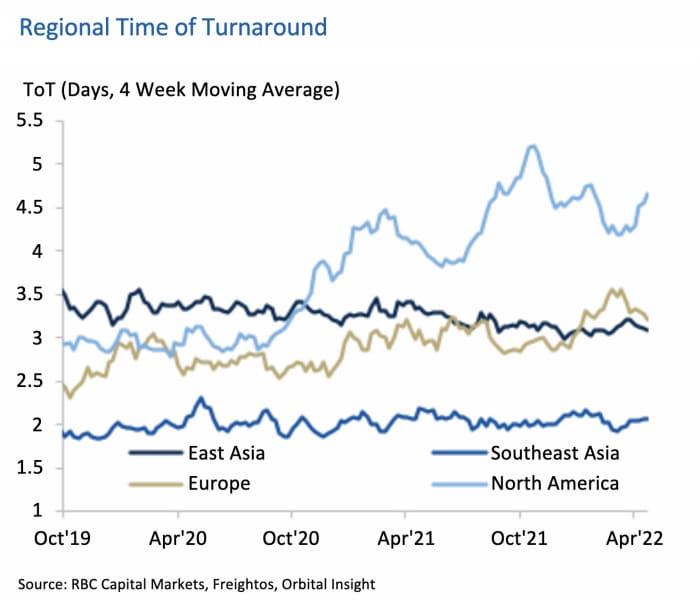

Instead, operational efficiency at both ports has “eroded over recent months.” With a queue of 19 vessels as of Monday, the current turnaround time is 6.9 days, compared with 3.4 days prior to COVID. “L.A. and Long Beach should be doing better by using this opportunity to completely reset and clear the bottlenecks, but are not: That’s what’s gone global,” Tran said.

Source: RBC Capital Markets, Freightos, Orbital Insight

Off the coast of China, 344 ships were awaiting berth at the Port of Shanghai, reflecting an increase of 34% over the past month, according to RBC’s report. It currently takes 74 days longer to get goods from a Chinese warehouse to U.S. warehouse, a route that used to take 37 days.

Meanwhile, ships from China are showing up four days late, on average, at European ports — which, in turn, is producing an empty container shortage for ships going from Europe to the U.S. East Coast. To prevent canceled bookings, both ships and containers must be available at the right time and place, Tran and Evans said.

Source: RBC Capital Markets, Freightos, Orbital Insight

Due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, several major shipping lines have suspended transportation into the Baltic and Black Seas. The aggregate turnaround time for the three largest European container ports — Rotterdam, Antwerp and Hamburg — are currently 8%, 30% and 21% above their five-year normal levels, according to RBC’s report.

On Tuesday, U.S. stocks struggled for direction earlier in the day before finding traction. The S&P 500 was up around 0.8% in the afternoon, while Dow industrials

DJIA,

and the Nasdaq Composite

COMP,

were higher by 0.5% and 0.3%, respectively. RBC’s equity analysts have mapped out key levels to watch and see 3,850 as the next rung down the ladder for the S&P 500 SPX.

Read: Stocks may keep sliding until institutions join retail investors in capitulation, this firm says