This post was originally published on this site

CHAPEL HILL, N.C.—The current slope of the yield curve tells us remarkably little about the odds of a recession and even less about the stock market’s prospects.

That’s important to keep in mind, given the huge amount of attention the yield curve has received over the last couple of weeks. Based on the frenzy of Chicken Little pronouncements earlier this week, you’d think the economy is about to collapse because the yield curve briefly inverted this week, when the 2-year Treasury yield rose above the 10-year yield.

A “just the facts” assessment of the data paints a far different picture. At most, what has happened to the yield curve over the last month increases the odds of a recession by a few percentage points. And those odds in any case remain low.

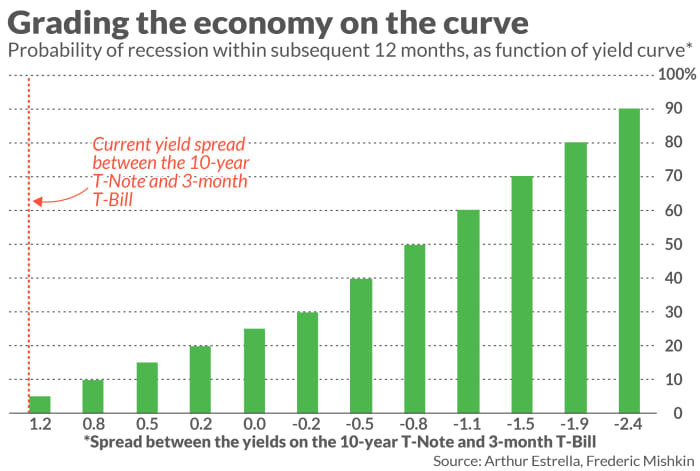

Consider one of the first studies to formally measure how the slope of the yield curve affects the odds of a recession. Entitled “The Yield Curve as a Predictor of U.S. Recessions,” it was conducted by Arturo Estrella (currently an economics professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic and, from 1996 through 2008, senior vice president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank’s Research and Statistics Group) and Frederic Mishkin (a Columbia University professor who was a member of the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors from 2006 to 2008).

For their study, the professors defined the yield curve as the difference between the yields on the 10-year and 90-day Treasurys. Based on the econometric model they constructed, the current yield curve translates into a recession probability of less than 5%. This is illustrated in this chart:

These low odds are caused in part because the 10-year versus 90-day yield curve is nowhere close to being inverted currently. In contrast, the 10-year versus 2-year curve is currently close to zero, having gone briefly negative earlier this week. But even if we were to insert this 10-year versus 2-year difference into the professors’ model, the odds of a recession would still be no more than 25%, having grown no more than 5 percentage points over the last month.

And while a 25% probability of a recession might alarm you, it shouldn’t. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the U.S. economy has been in a recession 29% of the time since 1857. So even at 25% the current odds are lower than what we would predict based on nothing more than the historical average.

By no means is the Estrella/Mishkin study the only or the last word on the subject of the yield curve, which has received an enormous amount of academic attention over the last couple of decades.

One other study deserving mention was conducted by Duke University Professor Campbell Harvey; in his Ph.D. dissertation in 1986 he reported that when the yield curve stays inverted for a calendar quarter then the odds of a recession become very high.

Note that as of now, the 10-year versus 2-year yield curve inverted only briefly and only intraday. Harvey’s model won’t trigger a recession prediction until the curve inverts and stays there for three months.

The yield curve as a stock market predictor?

The yield curve tells us even less about the stock market’s

DJIA,

prospects.

To show this, I loaded into my PC’s statistical package the historical data for the 10-vs-2 year yield curve back to 1962 along with the S&P 500’s inflation-adjusted real return. I looked for any significant correlations between the slope of the yield curve and the S&P 500’s

SPX,

performance over periods ranging from the subsequent one month to subsequent two years.

I came up completely empty at traditional standards of statistical significance.

The bottom line? Unless and until the yield curve becomes significantly more inverted than where it stands currently, and especially if it then stays inverted for several months, the odds of a recession remain low. At least for now, there are far bigger things to worry about.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.

More from MarketWatch

The bond market’s recession warning isn’t fazing stocks — yet. Here’s why.

Inflation has lessons for a ‘very entitled generation,’ says BlackRock co-founder

U.S. corporate profits jump 25% in 2021 to record high as economy rebounds from pandemic