This post was originally published on this site

The U.S. stock market won’t necessarily perform poorly because of the Federal Reserve’s quantitative-tightening policy. (QT).

This is hardly the consensus view, which confidently holds that QT is bad for the stock market. But the job of a contrarian is to test the assumptions that everyone else takes for granted.

Upon doing so in this case, I discovered precious little evidence that QT will have a significant impact on the stock market. This doesn’t mean that the stock market won’t suffer in coming months. It just means you shouldn’t base a prediction of a decline on the Fed’s announced monetary policy changes.

Consider the relationship between money supply and the stock market. Though there are many different ways of defining the money supply, the conventional definitions are highly correlated with each other. I focused on M2, which includes cash, checking deposits and so-called near money that can be converted into cash with little difficulty. Try as I might, I found no statistically significant relationship between M2’s trailing growth rate and the subsequent return of the S&P 500

SPX,

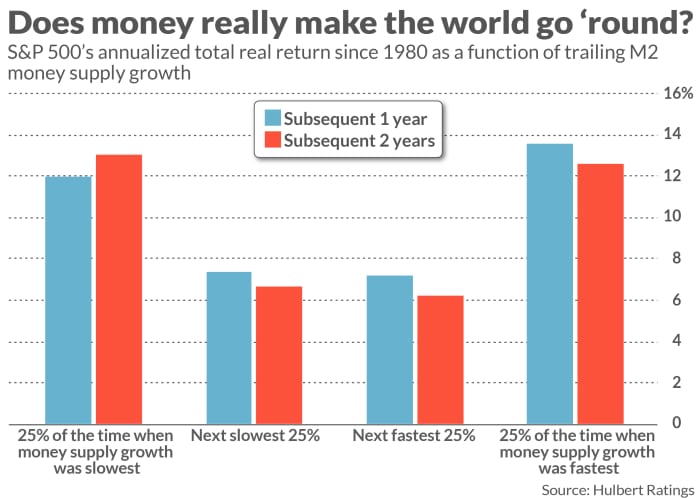

Focusing on monthly data back to 1980, I looked at M2’s trailing growth rate over periods from as short as the past 12 months to as long as the past five years, and the S&P 500’s subsequent performance over periods ranging from 12 months to five years. So that my results weren’t biased by a possible correlation between greater money supply growth and inflation, I focused on the S&P 500’s inflation-adjusted returns.

An illustration of what I found appears in the chart below. It segregates all months since 1980 into four groups based on M2’s rate of growth over the trailing 12 months. For each quartile, I average the S&P 500’s returns over the subsequent one- and two years. Notice that those returns are just as high for the slowest-money-supply-growth quartile as for the fastest — and lowest for the middle two quartiles.

What accounts for this surprising result? Some possible reasons include:

- The possibly offsetting effect of the velocity of money. I’m referring to the average number of times per year that money changes hands. If that velocity increases enough, a lower raw supply can end up being just as stimulating as an increase in that raw supply — and vice versa.

- The real money supply may have become unknowable, especially in recent years. Some have suggested that, due to the explosion of cryptocurrencies and other blockchain assets (such as NFTs), no one knows what the true money supply is right now. This suggestion seems at least plausible, since the total market cap of cryptocurrencies is several trillion dollars. And this total is volatile enough as to more than counteract any QT that the Federal Reserve might be contemplating. (This possibility in turn would mean that the Fed may have lost control of the money supply. The consequences of that would be huge, though I leave to others a full discussion of what those consequences would be.)

Interest rates and the Fed’s balance sheet

Yet perhaps I’m focusing on the wrong things. Might there be more significant correlations if I were instead to measure the relationship between the stock market’s subsequent returns and past changes in interest rates or the size of the Fed’s balance sheet?

I didn’t find any. That doesn’t mean interest rate changes or fluctuations in the Fed’s balance sheet don’t have any impact on the stock market. But their correlations aren’t stable or consistent. Sometimes, for example, the stock market will continue rising for several years during a rate-hike cycle and, when it finally starts declining in a big way, the Fed will immediately reverse course and start to cut rates.

Statistically modeling this correlation is anything but straightforward. This doesn’t mean that changes in the money supply, the Fed’s balance sheet, or interest rates aren’t important. They undeniably are. My point is that it’s not clear how you can use that undeniable truth to beat the stock market.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com