This post was originally published on this site

“‘In the short run, it’s hard to see how we get back to what we achieved in 2021.’”

That was Zachary Parolin, the author of “Poverty in the Pandemic: Policy Lessons from COVID-19,” speaking on a panel of experts Thursday about what can be gleaned from the U.S. government response to the coronavirus pandemic.

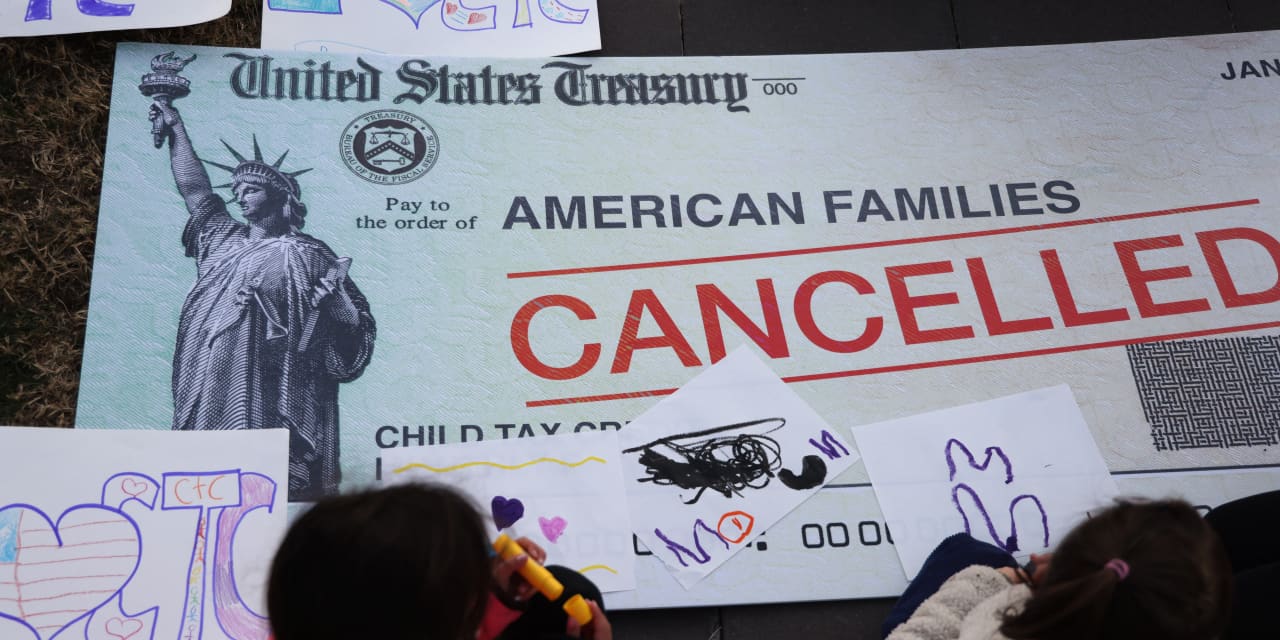

Their discussion came after the Census Bureau’s release last week of its annual poverty report, which showed that child poverty more than doubled from 5.2% to 12.4% from 2021 to 2022 as pandemic help expired.

Parolin, an assistant professor of social policy at Bocconi University in Italy and a senior research fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy, discusses in his book how the expanded child tax credit cut the monthly child poverty rate by one-third and contributed to the lowest child poverty rate in U.S. history; cut food insecurity for families with children by one-fifth; temporarily brought the U.S. child poverty rate in line with Germany’s; and more.

The expanded child tax credit gave eligible households with children up to $250 to $300 a month for a few months in 2021, helping lift 5.3 million people out of poverty, Census research shows. Certain families also qualified for stimulus payments in 2020 and 2021. Those policies led to the United States’ lowest poverty rate in history in 2021, Parolin stressed.

He said he didn’t see the “political stars aligning” again anytime soon to revive pandemic-response programs that came out of the American Rescue Plan and other legislation, which also included emergency rental assistance and pandemic unemployment assistance.

President Joe Biden’s attempt to pass his Build Back Better agenda, which would have included expanding or making some of those social-safety-net programs permanent, was largely stymied by Republicans and two Democratic senators, Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona.

But “in the long run, we’re building evidence about which policies work and which policies don’t” to help alleviate poverty, Parolin said.

After analyzing data about the effects of certain pandemic-inspired programs, Parolin said what worked were policies like pandemic unemployment insurance, which gave access to unemployment insurance to many more workers who would normally not have qualified for it.

Programs like the Paycheck Protection Program were less successful, Parolin said, and should be reformed “to better serve the needs of workers when the next economic crisis hits.” Very little of the $800 billion the government spent on the program — which was meant to help small businesses keep their employees on payroll during the pandemic — was used to protect the jobs of lower-wage workers, he said.

From the archives (July 2020): Over 500,000 businesses got PPP loans but are listed as retaining zero jobs, Treasury Department data show

Fellow panelist Wendy Edelberg, the director of the Hamilton Project and a senior fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, agreed. The PPP was “largely a waste of money,” said Edelberg, a former chief economist at the Congressional Budget Office.

The Hamilton Project also analyzed the effects of the pandemic policies beyond their effects on poverty, and Edelberg said she hoped “that policymakers don’t take the wrong lesson from the past couple of years — that we should provide less fiscal support during the next downturn.” She said she foresaw the inflationary effects of stimulus spending, but that “fiscal policy can do a lot more if it’s more targeted.”

Bradley Hardy, who teaches microeconomics and public finance at Georgetown University, said on the panel that the importance of books like Parolin’s — which posited that the underlying factors of poverty affected how people dealt with the disruption of the pandemic — is in showing that “everyone experienced the pandemic differently. … It’s something a lot of folks take for granted.”

Factors like intergenerational circumstances and the neighborhoods people live in all matter, he said, adding that the poverty rate for Black Americans jumped 6% between 2021 and 2022.

Additionally, he said, given the skepticism about government that he sees on his campus and elsewhere, “it’s important to document when policy is effective.”

But Jason DeParle, the New York Times reporter who moderated the panel, said it was also important to remember that the pandemic-era programs’ effects on poverty weren’t exactly intentional.

“It was a pandemic response,” he said. “It’s important to keep that in mind for the politics of the future.”

From the archives (May 2023): Food banks scramble to meet increased demand as COVID-era benefits expire