This post was originally published on this site

It’s International Women’s Day, but so much for coming a long way, baby — the gender pay gap has barely budged over the past 20 years.

What’s especially sad is that, while women launch their careers earning close to what their male colleagues are making, the divide between what men earn outpaces the income of their female counterparts as they continue in their careers.

So, what’s going on?

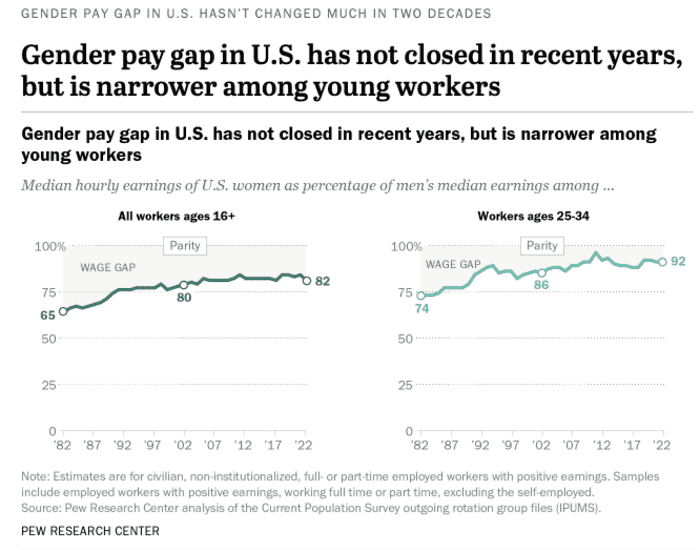

American women still typically earned just 82 cents for every $1 that a man made last year, which is depressingly close to what the gender pay gap was back in 2002, when women earned 80 cents to the dollar. That’s according to a recent Pew Research Center data essay in honor of Women’s History Month in March, and ahead of Equal Pay Day on March 14; the latter symbolizes just how far into the year U.S. women must work — in addition to what they worked the entire previous year! — to earn what men did year before.

And the gender pay gap has persisted in the 21st century despite the fact that women are more likely than men to have graduated from college, which should theoretically raise their earning power.

Related: Women need to save more, earlier and invest more aggressively for retirement – here’s why

First, it should be noted that the gender wage gap is better than it was in the 1980s; women earned just 65 cents to each buck that a man brought home in 1982. And the gap continued to shrink by 14 percentage points between 1982 and 2002 — but since then, wage gains for women seemed to stop.

Education gains may have accounted for some of that early success in shrinking the wage gap; in 1982, just 20% of working women ages 25 and up had a bachelor’s degree, compared with 26% of employed men. But by 2022, almost half of working women (48%) had a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education, compared with 41% of men. Yet higher education hasn’t continued to close the wage gap, perhaps because the wage gains from graduating from college have also changed (for both sexes) in recent years. Pew notes that the “college wage premium” that graduates enjoyed in the 1980s has slowed over time, which “likely reduced the relative growth in the earnings of women.”

Gender pay gap in U.S. has not closed in recent years, but is narrower among young workers.

Pew Research Center

So why do women still get paid less than men?

Pew notes that the gender pay gap is complicated, and there’s no single explanation for why shrinking that has “all but stalled” over the past two decades. But the report points out some factors that could be boosting men’s incomes while cutting into women’s earnings over time.

One notable point is that women generally begin their careers earning close to what their entry-level male peers are making, but then the rift between their incomes widens with age.

For example, women who were 25 to 34 in 2010 earned 92% as much as men their age, compared with 83% for women overall. But by 2022, when this group of women was now in the 37 to 46 age range, they earned only 84% as much as men the same age. And Pew saw this same pattern repeated with groups of women who were ages 25 to 34 in earlier years. And the report warns that this may well be the future for women entering the workforce now: they can start off earning salaries on par with men their age, but in a few decades, their male peers will probably out-earn them by wider and wider margins.

Young women begin their careers with closer pay parity to men their age — but the difference in earnings widens as they age.

Getty Images/iStockphoto

What’s more, a new LinkedIn report finds that the number of women in leadership positions in the U.S. workforce has increased just 1% in the past six years, suggesting women aren’t making the jump from entry level positions to leadership roles the way men are. And that’s despite being the majority of workers in many industries.

Pew’s research suggests that parenthood is probably one key factor here. Men generally enjoy a “fatherhood wage premium” that sees dads more likely to be in the labor force, working more hours each week, as well as enjoying an increase in pay compared to employed men without children. But on the flip side, women’s careers often take a hit once they become moms. Mothers ages 25 to 44 are less likely to be in the workforce than women the same age without kids, Pew notes, and those who remain employed tend to work fewer hours each week than women without children. This eats into a working mother’s earnings, helping to widen the gender pay gap.

Related: 9 tips for men to support the working women in their lives. Start by helping out at home.

And the pay gap certainly gets exacerbated by race. While women overall earned 82% as much as men last year, white women were slightly closer to parity at 83%. But Black women earned 70% as much as white men last year, and Hispanic women earned just 65% as much. (Asian women were closer to parity with white men, earning 93% as much.) While differences in experience, education and access are all in play here, as well, Pew notes that evidence of hiring discrimination against racial and ethnic groups also shuts out workers from opportunities to advance in their careers and earn more money.

Related: Biden’s State of the Union highlighted ‘near record-low’ Black unemployment. Here’s the full story.

What’s more, as many American women still disproportionately care for children, not to mention aging parents or other family members in need, this can also influence the types of jobs they can hold, and how far they can rise up the management ladder at those jobs, which contributes to the gender gap across some occupations (such as in STEM fields.) Women are underrepresented in STEM (aka science, technology, engineering and mathematics) occupations and in management or C-suite roles, which tend to pay more. And they are overrepresented in some of the lowest-paying fields, such as education, healthcare and personal care, which further widens the wage gap.

Moving forward, the report concludes that pay equity probably depends on increased workplace flexibility to help women juggle work and caregiving responsibilities, as well as “deeper changes in societal and cultural norms” that address gender stereotyping and discrimination.

More on MarketWatch:

The racial, ethnic and gender retirement gaps: How do we close them?

Inflation has hit women more ‘acutely,’ experts say. Here’s why.

Opinion: Pay transparency is good for workers — and employers get more of the top job applicants