This post was originally published on this site

When Vincent Davis opened the mail at his Brooklyn home one day this summer, an unusual set of documents caught his attention. Reading through the papers sent from an attorney’s office, Davis learned a portion of his paycheck would soon be seized each week to pay back a nearly $3,500 debt. He had seven days to respond.

The documents referenced a judgment entered against Davis 16 years earlier, in 2005, as part of a lawsuit filed to collect on a debt he apparently owed. It was the first he’d heard about the lawsuit. Davis, who at age 63 earned $16.50 an hour managing valets in a hospital parking garage, had been focused on helping his partner cope with the aftermath of a stroke and looking for a new apartment. He remembered little about the debt referenced in the letter.

But in the period between the date of the judgment and when Davis received the documents, the amount he allegedly owed ballooned from $1,421 to $3,435. The roughly $2,014 of interest was a consequence of the law in New York, where judgments accrue interest at a rate of 9%, well above market interest rates. Now, Davis was at risk of being forced to put 10% of his wages each pay period towards the debt even as the high interest rate meant the principal would likely continue to grow.

“I was barely making ends meet already and worrying about garnishment from your check — it’s scary,” said Davis. “It’s hard enough for me to remember yesterday or two days ago,” Davis added. Let alone “to remember 16 years ago, what they were talking about.”

Post-judgment interest is a feature of the nation’s complex debt collection system that has increasingly become a hotly contested battleground for creditors, loan buyers, and consumer advocates. The underlying judgments are often bought and sold by debt collectors who in many cases have the power to seize the wages and put liens on property of consumers, who sometimes only learn a judgment has been made against them years after a loan balance has started ballooning at a high interest rate.

In some states, consumer advocates have successfully pushed post-judgement interest rates lower, while in other states the debt collection industry has fought to maintain higher rates. As a result, where a debt collection judgment is entered can play a large role in whether it ticks up modestly or grows substantially. In states like New Jersey, the post judgment rate is as low as 1.5%, while in other states, like Massachusetts, rates are as high as 12%. In federal court, judgments are assessed at the one-year treasury constant maturity rate.

It’s consumers with low incomes who most often face these debt collection actions and high interest rates can cause the debt to balloon in a way that makes it hard to pay back, legal aid attorneys said. In some cases, the situation drives people to bankruptcy.

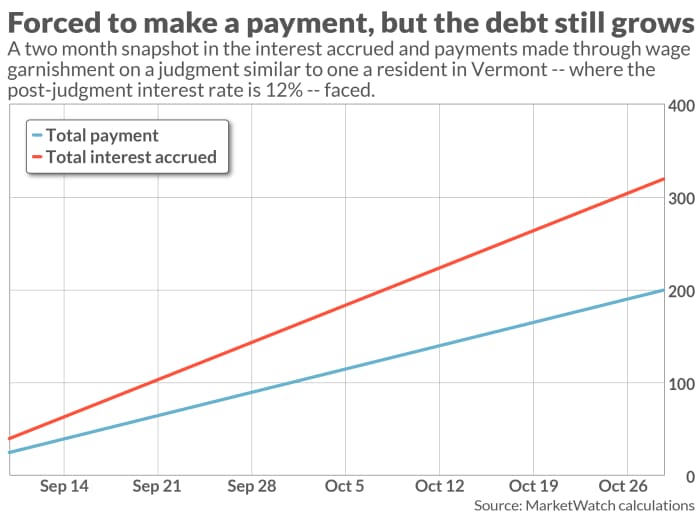

“For a consumer that can only make small payments, you could quickly end up in a situation where the debt itself is not amortizing because the interest rate is so high,” said April Kuehnhoff, a staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center. “This is an area where people can get tripped up and fall further and further behind unfortunately as they’re struggling to make ends meet.”

The reason behind charging interest on a judgment is mostly to compensate a creditor for the time after an unpaid judgment was issued when the money could not be used or invested. Richard Perr, a Philadelphia lawyer and member of the Association of Credit and Collection Professionals, noted that interest is applied to a variety of types of judgments, like personal injury judgments, not just those involving consumer debt.

“Ignoring or delaying satisfaction of a court-posed judgment is something that policymakers have determined is not beneficial to the rest of society,” Perr said. “By depriving the creditor of the principal amount, there’s an economic penalty that comes with that as determined by the state.”

But in many states, the current post-judgment interest rate is a vestige of a different era, a time when interest rates were broadly much higher. These abnormally high rates have the potential of creating a windfall for creditors and a mismatch between the rate at which a judgment grows and the return rate of any savings or investment vehicle a consumer might reasonably use today to raise money to pay the judgment.

Davis was only able to deal with his post-judgment debt surprise with assistance from New York non-profit legal services organizations like Mobilization for Justice. After being challenged in court, the company suing Davis couldn’t prove he’d been properly served with the original debt collection lawsuit in 2005.

“I was very, very happy that this was one less thing that I had to deal with,” Davis said.

***

This past spring, Maria Perez logged into her payroll portal at work and was stunned to learn that her next salary payment would be dinged by more than $200.

“I live paycheck to paycheck,” Perez said. “I know exactly what I’m getting and I look because that’s how I live.”

Perez, 61, lives in the Bronx with her mother, who is her 80s, and her 25-year-old son. She stretches the income she earns as a teaching assistant at a New York City public school to cover rent, food and other expenses for the three of them. In 2021, paraprofessionals, as workers like Perez are known, earn a maximum of $47,723 a year in New York City public schools — so she knew that the more than $200 missing from her next check would have an impact.

“It was food on my table,” she says.

Maria Perez was surprised to learn her wages would be garnished over an alleged debt she never remembered owing.

Courtesy of Maria Perez

Hunting for the reason behind the disappearing money, Perez looked further down on her paystub and found that the missing funds were the result of a garnishment. She called the number of the New York City marshal responsible for executing the garnishment, and was told it was related to a judgment over a roughly $15,000 debt. “I’m like ‘but from where?’” Perez remembers asking the woman on the phone. The garnishment paperwork was the first time Perez had heard about the debt, she said.

Perez learned that when she was first sued over the money in 2005, the alleged credit card debt was $5,637. Now, her income was at risk of being garnished to pay back a judgment worth $15,140. New York State’s 9% post-judgment interest rate had caused the debt to balloon in the intervening years. The person on the other end of the phone told Perez she had the right to fight the garnishment, but she had to figure out how she would do it.

The next business day, Perez went to the courthouse. She spoke with a courthouse staffer who didn’t provide much help. “I guess she was looking for legal terms, legal terms which I don’t know anything about,” Perez said. Like many consumers facing a debt collection lawsuit or judgment, Perez didn’t know much about the process and didn’t have a lawyer to help her. On the other hand, some debt collection law firms have high volume practices and file thousands of lawsuits a year.

Perez made her way to an office in the courthouse, where she found legal help in the form of a phone number posted on the door. She took a picture with her phone and called the number. A legal aid volunteer attorney called her back. As a result, Perez had an attorney on the phone talking her through the online proceedings, but the process was still intimidating, she said.

“It was very hard and frustrating for me to even get through the link to get to the hearing,” she said. “This never happened to me before and then all of the sudden I’m trying to defend myself.”

During the weeks Perez dealt with the case, she became depressed and lost sleep. Perez found it difficult to manage the legal situation while at work. Her efforts to get in touch with people, for example, distracted her from her students. Perez’s principal even noticed and asked if she needed help.

Ultimately, the judgment was dismissed. The debt buyer that had purchased the debt could not prove Perez had ever been properly served with the initial lawsuit by mail more than a decade ago. When she showed up virtually to court, Perez remembers the creditor’s attorney saying that he had better cases to fight. Though Perez was relieved to get rid of the garnishment threat, the nonchalance with which the other side treated her case made her angry.

“You make my life miserable,” Perez said. “It’s upsetting that you make people go through this.”

***

Perez’s life was made more miserable because she lived in New York, where the statute of limitations on a judgment is 20 years, during which time it can build at a 9% rate, sometimes without a consumer being aware of it. In some states where the post-judgment interest rate is high, advocates have gotten lawmakers to blunt its impact on consumers. In New York, for example, this summer lawmakers passed a bill sponsored by state Senator Kevin Thomas that would bring the post-judgement interest rate in the state down to 2%. It’s awaiting the signature of Governor Kathy Hochul, who is reviewing it, according to a spokesman. A coalition of 33 legal services and advocacy organizations sent the governor a letter in November urging her to sign the bill.

But advocates have not been successful everywhere.

For years, Jean Murray, a staff attorney at Vermont Legal Aid, has been concerned about the post-judgement interest rate in her state of 12% — one of the highest rates in the country. She started lobbying lawmakers on the issue in 2017. A bill that would have suspended or reduced interest on judgments related to some consumer credit card debt passed the state’s house of representatives in 2018. Ultimately, “it didn’t get anywhere,” Murray said.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Murray recalls working with one client starting in 2016, a hotel housekeeper who came to Murray when she discovered a debt buyer was suing her for the renewal of a judgment. (In Vermont, the statute of limitations on a judgment is eight years, but a creditor can file to renew that judgment before the eight years is up.) The original debt of $17,319 was related to medical expenses the woman put on her credit card in 2008 when her husband, who had since passed away, was sick. The woman paid $9,575 towards the debt between 2008 and 2015 through wage garnishment, but by 2016 the debt had ballooned to $22,685. The experience made the woman “petrified to go into debt” again, Murray said, so when an ailment started to plague her she didn’t seek medical treatment.

“Before I could finish her representation she had died,” Murray said.

For years, consumer advocates have unsuccessfully been pushing Massachusetts lawmakers to bring the state’s 12% post-judgement interest rate down, among other consumer-friendly reforms to the debt-collection process. “We see it as a cycle of poverty where poor people just can’t get out,” Nadine Cohen, managing attorney, consumer rights unit at Greater Boston Legal Services, said of the consequences of the 12% interest rate. The legislation is still pending and advocates are hopeful it will pass this year, Cohen said.

In many states, the purpose behind laws establishing interest on a judgment is to compensate a creditor for the time when they couldn’t use or invest the money, according to a law review article by Christine Abely, a faculty fellow at New England Law, Boston law school. In a few cases, another goal of the statute may be to incentivize debtors to pay the funds quickly, Abely said.

But when a state’s fixed interest rate is much higher than the market rate, which is the case today in many states, or even when there’s a high premium attached to a rate that tracks the market, the interest would likely overcompensate the collector, and “grant it a windfall; that windfall would be largest in times of extremely low market interest rates,” Abely wrote. The high rates on the judgments and the low rates in the market mean that if consumers can afford to invest to pay off the judgment, that money isn’t growing as fast as the judgment.

Massachusetts lawmakers haven’t changed the statutory post-judgement interest rate since 1982, Abely found, a period of historically high rates. Though interest rates have plunged since those days, the rate has not been updated.

Consumer advocates in other states have had more success. Ashlee Highland, a supervising attorney at CARPLS Legal Aid in Chicago, first became concerned about the impact of post-judgement interest on consumers in 2006, when Illinois’ rate was set at 9%.

At the time, Highland was supervising the collection desk in one of the busiest courtrooms in the country and the desk would see about 30 clients a day dealing with judgments on payday loans, credit cards and other debts. She’d have to tell them that the collector was entitled to interest on the judgment of 9% and that the court couldn’t modify the rate.

In other scenarios, she’d encounter clients who were having their wages garnished over these debts, but it was “just going straight to interest,” Highland said. “They were never going to pay off the balance.”

So Highland decided to get involved in an effort to get the law changed. Will Guzzardi, the Illinois state house representative who sponsored the bill, said stories from consumer advocates about how these judgments, which targeted low-income people and predominantly people of color could “just hang out there,” seemed “pretty unfair.” He saw it as his responsibility as a lawmaker to limit the ability of industry to engage in “predatory behavior” against struggling residents.

Highland and other consumer advocates wanted to bring the rate down to a fixed 2% on judgments for amounts under $50,000 that do not involve bodily injury or death. Creditor industry representatives spoke in opposition to the measure in a 2018 hearing.

But through negotiations with the association of lawyers who represent creditors, the two sides were able to agree on a rate of 5% for judgments worth less than $25,000, which the legislature was willing to pass into law.

Robert Markoff, an Illinois-based creditor attorney who was involved in the negotiations, said the back and forth was just one example of the “natural tension” that exists between consumer advocates and collectors.

“We just compromised,” he said. “If consumer groups had their way there would be no interest, if creditors had their way interest would be 25%.”

In Washington, statewide advocacy pushed the legislature to lower the interest rate from 12% to 9% in 2019. Nine percent is “where it came out of the legislative machine at,” as Scott Kinkley, an attorney at the Northwest Justice Project legal aid organization, put it. One proposal would have set the rate as low as 7.5%, but was abandoned after lobbying from the collection industry, the Seattle Times reported at the time.

***

Legal aid attorneys across the country say post-judgment interest is part of a long process that’s stacked against consumers. Over the past few decades, state civil courts have primarily become a venue for creditors and debt buyers to collect debts. Between 1993 and 2013, the debt collection cases being filed each year grew from 1.7 million to 4 million, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts. As of 2013, roughly one in four civil cases was related to debt collection.

Research indicates that between 2010 and 2019, in many many jurisdictions where data are available, just 10% of defendants facing a debt collection lawsuit had representation, according to Pew. More than 70% of debt collection cases are resolved through default judgment, according to data in several jurisdictions examined by Pew, meaning the consumer has not even appeared in court to defend themselves.

Defendants may not show up because of work, childcare or other conflicts. But in many cases, they don’t show up because they’re not aware they’ve been sued, legal aid attorneys say. Since ownership of a debt likely changed multiple times by the time a collector goes to sue a consumer, they may not have the most up-to-date address or other contact information.

In addition, litigation, and regulatory scrutiny suggest that in some cases the process servers hired by debt collectors don’t make much effort to provide consumers with notice of the lawsuit — a phenomenon consumer advocates refer to as “sewer service,” because the process server theoretically throws the lawsuit into the sewer. Servers are typically required to file a court affidavit with information about where and how they served the lawsuit.

“Between 1993 and 2013, the debt collection cases being filed each year grew from 1.7 million to 4 million, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts. As of 2013, roughly one in four civil cases was related to debt collection. ”

In a conversation with a client facing an issue with a default judgment, it became clear to Desirée Nguyen Orth how little effort the process server put into notifying her client. The director of the consumer justice clinic at East Bay Community Law Center in Berkeley Calif., was going over the proof of service document with the client. The client did not live at the address where the service occurred and the description of the person served was generic, describing a female recipient between 5’2 and 5’8, between the ages of 25 and 35 and weight between 160 and 200 pounds.

“My client laughed,” Orth said. When she asked why the description was funny, he told her there was no one in that home who weighs under 400 pounds.

It’s rare that there’s such compelling evidence available that a consumer wasn’t served, Orth said. Typically, if a client believes they haven’t been notified of a suit, she advises them to find receipts, location and date-stamped photos, or any other type of documentation that would indicate they weren’t at the address the server visited at the time they visited. That task can be particularly challenging because creditors will wait several years before filing their case and it’s hard for clients to remember exactly where they were so long ago, Orth said.

Exacerbating both the impact of the high interest rate and the spotty service is that in many states these lawsuits and judgments have relatively lengthy statutes of limitations. In addition, they can often be renewed. “If you don’t get legal services assistance, people end up paying these judgments and they’ll pay them their entire lives because the interest keeps accruing,” said Carolyn Coffey, director of litigation for economic justice at Mobilization for Justice.

Orth and other consumer attorneys suspect that creditors wait out these periods for as long as possible in part to see if the consumer gets to a phase in life where they may have more income to put towards the judgment and in part to let the interest accrue.

“That ensures both the ability to collect and a high amount,” she said.

Donald Maurice, legal counsel for the Receivables Management Association International, said the creditors and debt collectors that are members of his organization don’t sit on judgments and any interest that would accrue on them during the intervening period wouldn’t offset collection costs. Some smaller companies in RMAI’s membership have expressed concern about a provision in the New York bill that would retroactively apply lower rates to past judgments that haven’t been paid because it could cost them to recalculate those judgments, he said.

“Persons who have judgments against them are financially distressed, the problem is not trying to collect more on the judgment, the problem is trying to collect any amount,” he said. “It just doesn’t make sense that anyone who is practicing good compliant business practices is going to want to sit on judgments to accrue interest.”