This post was originally published on this site

High-quality bonds should hold up better than stocks, right? Particularly if defaults aren’t really the worry.

But that hasn’t been the case lately for debt issued by many Fortune 500 companies, a sector hit notably hard since the Federal Reserve shifted its stance to urgently cool inflation.

U.S. investment-grade corporate bonds, the debt sold by many big companies in the S&P 500 index

SPX,

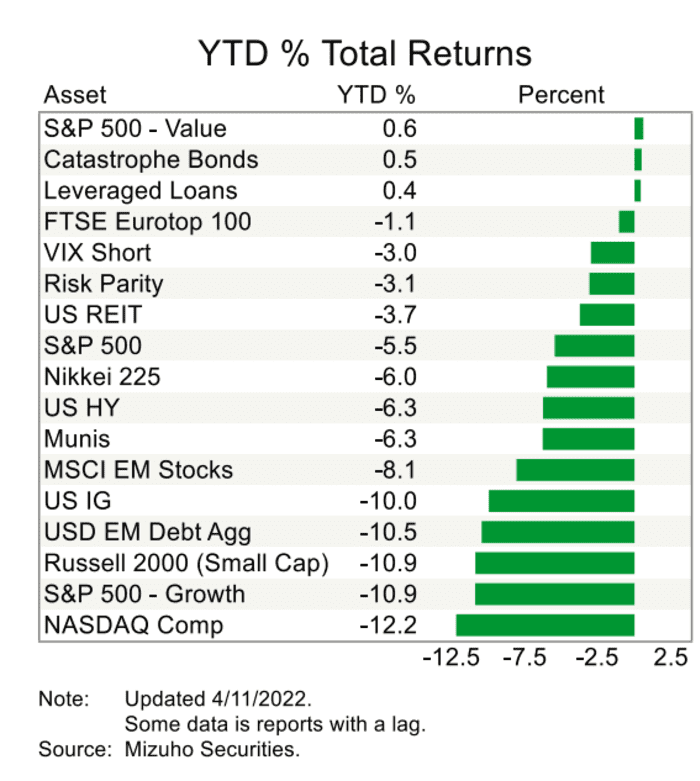

have registered a negative-10% total return so far in 2022 (see chart), after booking their worst quarterly loss since the global financial crisis, according to Mizuho.

Few financial assets are registering even modestly positive returns so far in 2022.

Mizuho Securities

The rout in high-quality corporate bonds compares with a roughly minus-6% total return for the S&P 500 index

SPX,

and negative-6% performance for bonds issued by municipalities and high-yield companies.

“We are in a tough environment,” said Jack McIntyre, a portfolio manager at Brandywine Global Asset Management. “Bonds are selling off, equities are selling off. The real return on cash is negative.”

McIntyre expects bonds to be a “great buy” at some point, given the steady march higher in yields, even though he expects bumps along the way.

For one thing, the Fed needs to figure out how much to increase its policy rate to help tamp down inflation that’s at 40-year highs, while also shrinking its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet, all without hurting the economy.

See: Yellen says not impossible for Fed to engineer soft landing for U.S. economy

Many on Wall Street now expect the Fed to hike the fed-funds rate by a half-point in May, while also kicking off “quantitative tightening,” or reducing its balance sheet, at its swiftest pace ever.

The hope is that rates, including the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield

TMUBMUSD10Y,

will stabilize and help provide bonds with a firmer footing. Corporate bonds and other debt that comes with credit risks are priced at a spread, or premium, above the risk-free Treasury rate, which has shot up dramatically this year as Fed officials have talked tougher on inflation.

A turning point?

Corporate defaults have remained low, following an early deluge during the pandemic, and could stay that way for a few years, given the extremely low-cost financing many big companies secured in the past two years.

That doesn’t make it easier for investors holding trillions worth of bonds at low coupons that aren’t due to repay for roughly a decade, or longer in some cases.

“I think individual investors are still licking their wounds, given the negative total returns,” said Travis King, head of investment-grade credit at Voya Investment Management. “But we think with around 4% yields it starts to look like a better entry point, particularly if there is stability in the Treasury market.”

King also said other positive signs have emerged in the form of an uptick in overnight buying activity from Asian investors in high-grade corporate bonds.

“That’s definitely supported our market,” King said, although he also worried about increased hedging costs that could dampen foreign appetite. “If the Fed ends up moving rates higher by 50 basis points at multiple meetings, those hedging costs become more expensive.”

Inflation path is everything

A big focus going forward will be the trajectory of inflation, after U.S. consumer prices rose 8.5% year-over-year in March, the fastest pace since January 1982.

David Norris, head of U.S. credit at TwentyFour Asset Management, sees hope in easing prices for used cars and other segments of the consumer-price index, but also potentially greater stability with the 10-year Treasury rate around 2.7%.

“At the end of the day, I think we are close to the peak in inflation at 8.5%,” Norris said, by phone. While the Fed plans to front-load rate hikes this year, he also expects that over the next two quarters the central bank will need to re-evaluate the state of the economy, and perhaps decide the policy rate won’t need to be adjusted aggressively higher.

“Over the course of time, we will see how the economy is able to withstand rate hikes,” Norris said.

Brandywine’s McIntyre warned of the unusual times. “It’s kind of in a Volcker moment, and marry that with a Putin moment,” he said, referring to the spike in oil prices

CL.1,

and in other commodities following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the early 1980s recession triggered by former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker’s battle against high inflation.

“Something is going to break,” McIntyre said. “Ideally, it is inflation, then it means the Fed stuck the landing.”