This post was originally published on this site

Demography is destiny, the 19th century French philosopher Auguste Comte is quoted as having said. If so, then the United States’ long-term economic prospects are relatively bright — relative to that of Russia and China, at least.

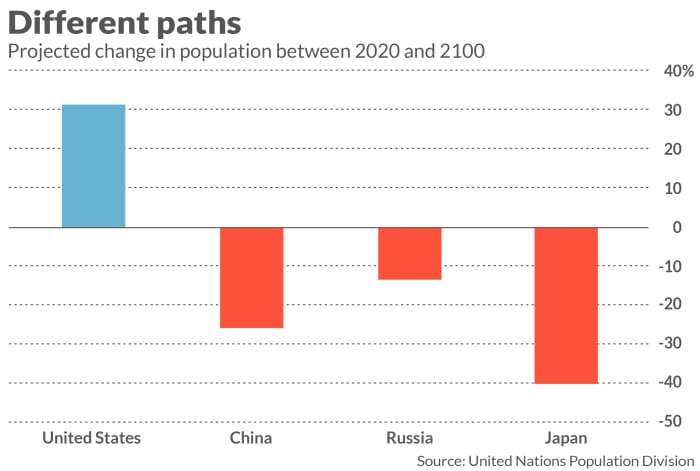

That’s because these three countries’ populations are projected to take dramatically different paths over the remainder of this century, as you can see from the chart below. The United Nations Population Division projects that the U.S. population will be 31% higher in 2100 than in 2020, while Russia’s population is projected to be 14% smaller and China’s 26% smaller.

Differences of this magnitude should have a huge impact. As Loretta Mester, president and CEO of the Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank, put it at a 2017 conference when summarizing academic research into demography’s impact on the economy: “Demographic change can influence the underlying growth rate of the economy, structural productivity growth, living standards, savings rates, consumption, and investment; it can influence the long-run unemployment rate and equilibrium interest rate, housing market trends, and the demand for financial assets.”

This isn’t to say that the relationship between population growth and economic growth is simple or straightforward. Just as a shrinking population can put downward pressure on economic growth, so can a population that is growing too fast. Productivity also plays an outsized role in whether population growth plays a positive economic roll. As a general matter, economists tend to agree that in order to grow, economies need an expanding base of both workers and consumers — a larger population, in other words.

Though the U.S. population growth rate looks good in comparison to Russia’s and China’s, it’s hardly something to celebrate. At just 0.3% on an annualized basis, it’s barely enough to keep the U.S. population from shrinking. Coincident with this low growth rate is the rise of an aging population, which puts increasing pressure on the working-age population to fund Social Security and other social programs.

But if the U.S.’ demographic destiny isn’t exactly rosy, Russia’s and China’s are downright dismal. This fate has hardly been lost on those countries’ leaders. It played a big role in China’s decisions over the past decade to move to a two-child, and then three-child, per family policy.

With Russia, some have suggested that part of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s calculus in continuing to pursue an otherwise disastrous invasion of Ukraine is an acute awareness of Russia’s eventual demographic demise. Describing Putin as “haunted” by that prospect, The Times of London columnist Dominic Lawson has argued that “population decline is the driver of the war.”

Investment implications

Though focusing on investments seems indecent in the context of the horrors of the Russia-Ukraine war, such a focus provides an additional perspective on demography’s significant long-term impact. Consider Japan’s stock market, which has faced significant demographic headwinds for several decades now. As the chart above indicates, these headwinds persist for many more decades; Japan’s population in 2100 is projected to be 40% lower than where it stood in 2020.

Note carefully that population size is not helpful for stock-market timing — over not just the short-term but over longer-term horizons of up to a decade or two. Over periods up to that length, researchers have found, the stock market appears to respond more to whether the working age population is growing relative to the very young or very old cohorts. This is one reason why a bull market lasting a decade or two can occur even in a country facing a century of demographic decline.

Population growth becomes relevant for investment horizons longer than a decade or two — such as when investing for retirement. Perhaps the most obvious investment implication is the importance of international diversification into less-developed economies. Almost all of the world’s net population growth between now and the end of the 21st century will be concentrated in countries that currently are classified as less developed. The United Nations’ Population Division projects that these countries’ total population will be 48% higher in 2100 than in 2020, in contrast to no net change among countries classified as more developed.

Individual regions will experience even more starkly different population growth paths. The United Nations projects that Africa’s population in 2100 will be 231% higher than in 2020. Asia, in contrast, will experience just a 2% increase over that period, while Europe’s will decline.

Even while acknowledging that the relationship between population growth and the economy and stock market is complex and sometimes inscrutable, it’s clear that focusing your equity portfolios on the U.S. in particular, or more broadly on the world’s currently most-developed countries, will miss some of the most profitable investments of the next century. After all, every “more developed” country was, at some point in the past, a “less developed” one.

According to the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2022, for example, Finland moved from the “emerging” to the “developed” category in 1932. Japan made the shift in 1967; Spain in 1974; Hong Kong in 1977, Singapore in 1980, and Israel in 2010. It’s a good bet that there will be many more countries will undergo a similar graduation at some point this century, and it would be short-sighted to miss out on them.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: A majority of workers have confidence in Social Security. Should you?

Also read: Saving for retirement? These are the only two stock funds you’ll ever need