This post was originally published on this site

Jumping the gun is dangerous when anticipating the timing of the Fed pivot. I’m referring to the guessing game that many on Wall Street are playing, which focuses on when the U.S. Federal Reserve will stop raising rates and begin to reduce them — pivoting, in Fed speak.

The reason it’s important to play this game, they argue, is that the stock market is a forward-looking and discounting mechanism. That implies the U.S. stock market will hit bottom and start rising in advance of a pivot.

While there is a certain amount of plausibility to their argument, history does not support it. The stock market typically doesn’t bottom out until after the Federal Reserve begins to reduce interest rates. I count 13 major pivots over the past seven decades, and only in five of them did the stock market bottom in advance of the move.

Furthermore, if you date the Fed’s pivot to when it begins to reduce the pace of interest rate increases, then there would have been even fewer occasions in which the stock market hit bottom in advance. That’s particularly relevant to today’s market, since stocks have been rallying in recent weeks on the expectation/hope that the Fed at its December meeting will raise rates by 50 basis points as opposed to the anticipated 75 basis points.

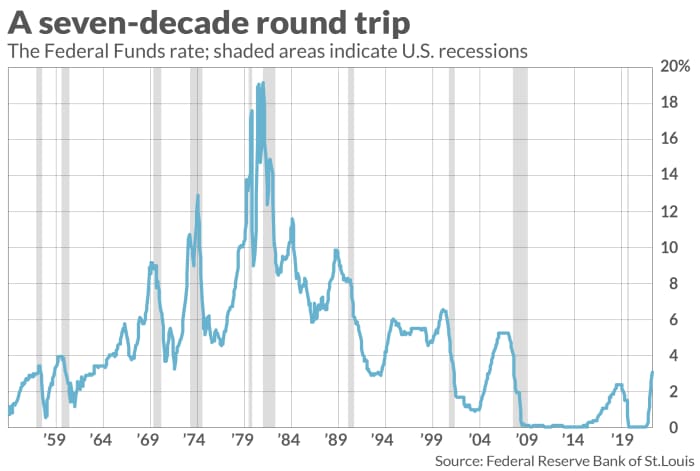

To measure the stock market’s reaction to Fed pivots, I analyzed all occasions since the 1950s in which the federal funds rate started declining after a sustained uptrend. The federal funds rate is the rate at which banks lend money to other banks on an overnight basis. It is perhaps the single best indicator of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy, since it uses its open-market operations to keep the actual overnight rate within a target range.

The 13 pivots I analyzed are evident by the peaks in the chart above. For each, I focused on the Dow Jones Industrial Average’s

DJIA,

lowest close over the two-year period beginning one year prior and lasting until one year later. Averaging all 13 occasions, the Dow hit its low one month after the date of the Fed pivot.

Of course, this is an average, and in some cases the Dow did hit its low prior to the pivot. But these were in the minority — just five of the 13 cases.

Pivots and recessions

There’s one big reason why the stock market doesn’t always bottom in advance of pivots: The Fed is often slow to react, pivoting only after its rate-hike cycle has pushed the economy to the brink of a recession. In such cases, the good news of lower interest rates is more than offset by the imminent reduction in corporate earnings caused by recession.

This phenomenon is illustrated in the chart above. The shaded regions indicate when the U.S. economy was in a recession, as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (the semi-official arbiter of when recessions begin and end). Notice the tendency for recessions to begin after the Fed pivots.

The Fed’s depressing track record provides the context for the current debate over whether the Fed has already doomed the U.S. economy to soon enter into a recession. If it has, then the timing of the Fed’s pivot becomes less important to stock market investors than the severity of the imminent economic downturn.

The bottom line: In order for it to be worthwhile to guess when the Fed’s interest-rate pivot will occur, you first have to guess whether a recession is imminent and, if so, its length and severity. No wonder there’s no easy or straightforward way of exploiting the uncertain timing of a Fed pivot to make money in the stock market.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: A recession akin to 1969-1970 awaits U.S. next year, economist warns

Plus: ‘We see major stock markets plunging 25% from levels somewhat above today’s,’ Deutsche Bank says