This post was originally published on this site

Gang Hu, a 20-year veteran trader with New York hedge fund WinShore Capital, is warning that a continuing climb in the U.S. dollar risks leading to hotter-than-expected U.S. inflation, a counterintuitive view that’s not widely shared.

If the scenario envisioned by Hu pans out, it would flip the script on the more traditionally held notion that a stronger dollar acts as a brake on inflation, by curbing demand and driving down the price of imports. The dollar has been on a tear for over a year, benefiting from its safe-haven appeal, expectations of higher U.S. interest rates, and the view that the U.S. economy should hold up better than other parts of the world.

One of the biggest unknowns to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic is how much longer persistently high inflation in the U.S. and world-wide will continue. Financial markets have been adjusting this week to the prospect of a more stagflationary outcome in the U.S. with stocks selling off, yields rising, and the ICE U.S. Dollar Index

DXY,

hitting some of its highest level in 20 years. Most traders aren’t positioned yet for an environment in which inflation either keeps rising or doesn’t meaningfully come down through next year.

“I think I’m very alone,” Hu, 49, said via phone on Friday. “But it really boils down to whether inflation expectations are coming unanchored, and I’m sensing that they are.”

When expectations are anchored, a stronger dollar is seen as a deflationary force because businesses can focus on deteriorating demand and are quick to cut prices. But when they become unanchored, those expectations translate into “more people believing in inflation and more people feeling free to raise or accept higher prices,” he says.

The graph below reflects how the U.S. Dollar Index has risen alongside the 10-year break-even rate, according to Hu.

Source: Bloomberg LP

Hu acknowledges three different possible interpretations for this dynamic. One is that inflation is leading the dollar higher; in other words, the U.S. currency’s strength merely reflects the need for policy makers to lift U.S. interest rates and stamp out inflation. The second is the view that the moves are merely coincidental. And the third is what he calls “a bit controversial.”

It’s the idea that the stronger dollar “could signal future market destructions” outside the U.S. and lead inflation higher than financial professionals think. His logic goes as follows: A stronger dollar tends to hurt investors and businesses outside the U.S. the most, raising dollar-denominated liabilities of foreign nonbank borrowers, while acting as a potentially negative force on the balance sheets of non-American corporations. That much most economists can agree on.

What Hu sees differently than economists or traders is that this negative impact outside of the U.S. could hit the supply side of the demand-supply equation quite hard. A case in point is China, the top supplier of goods imported into the U.S. When China went into recent COVID-19 lockdowns, the market “took it as a supply destruction event,” Hu says. And the 10-year break-even rate kept going higher.

His concern is that businesses could see the removal of supply competition and hike prices even when demand is impaired. The takeaway is that if the dollar continues to appreciate from here, he says, inflation could keep running hot despite the central bank’s efforts to contain it.

Historically speaking, the exchange rate and U.S. inflation tend to move in opposite directions. Inflation measures typically fall when the dollar’s exchange rate is rising, and they rise when the exchange rate is falling, though that relationship became more tenuous during the first half of the 1980s, when the Fed was still trying to stomp out inflation under then-Chairman Paul Volcker.

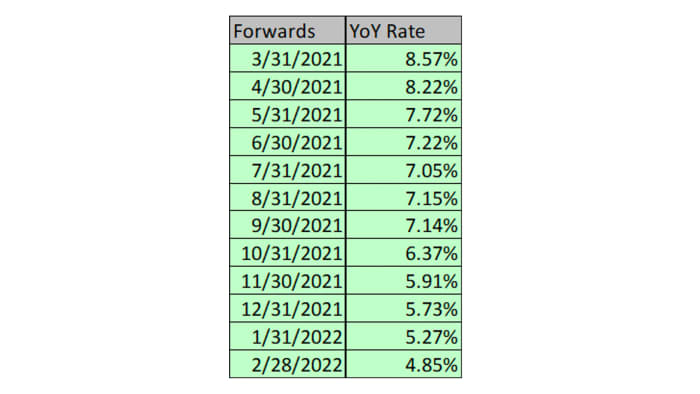

For now, traders and economists alike foresee a benign inflation path for the U.S., one in which inflation comes down, albeit not necessarily to as low as it was before the pandemic. Traders of derivative-like instruments known as fixings expect the annual headline U.S. inflation rate, based on the consumer-price index report, to fall below 5% by early next year from 8.5% as of March. The chart below shows how much the annual rate is expected to rise versus year-earlier periods.

Source: Bloomberg

What makes Hu’s views particularly interesting is that he, too, had been in the lower-for-longer camp on inflation, with the view that price gains were bound to come down at some point. Previously, Hu has been an inflation portfolio manager at bond fund giant Pacific Investment Management Co., or Pimco, a trader at BlueCrest Capital Management, and global head of inflation trading at Credit Suisse

CS,

But his views have taken a 180-degree turn over the past year. His latest thoughts about the dollar’s possible impact on inflation is “a non-base case, but one that warrants more probability distribution. It’s one that nobody is positioning for,” he says.

“I can’t say how big the miss is by traders,” Hu said. “Even the direction is counterintuitive, so that if the direction turns out to be correct, most of economic theory needs to be rewritten. I don’t even know how to put a scale on it, but the risk is higher than what the market is calling.

“Most traders are in one of either two camps: Sell everything and head back into cash, or selectively buy stocks and inflation-linked bonds. I think long-term asset allocation frameworks should err on the side of needing to be somewhat invested in inflation-sensitive assets.”

As of Friday afternoon, U.S. stocks traded sharply lower amid heightened stagflation fears. Dow industrials

DJIA,

were down by more than 350 points in the final hour of trading, while the S&P 500

SPX,

was lower by 1.3% and the Nasdaq Composite

COMP,

was off 2%. Meanwhile, 5- to 30-year treasury rates continued to rise further above 3%.