This post was originally published on this site

How much will you spend in retirement?

Despite what you’ve been led to believe, your spending is going to decline on a real basis – after adjusting for inflation – about 1.8% per year over the course of your retirement, according to Explanation for the Decline in Spending at Older Ages, research published by several authors affiliated with the RAND Corporation. Watch Explanations for the Decline in Spending at Older Ages.

Now, that might not sound like very much, said Hurd. But if you begin retirement at age 65 and survive until age 95, you will have reduced spending by quite a bit. Think of it, he said, as the “reverse of compound interest.”

And what that means, among other things, is that you might be saving more for retirement than you’ll need. “The so-called retirement crisis, it’s there for some people,” said Michael Hurd, a senior principal researcher at the RAND Corporation and a co-author of the research. “But it’s not a population-wide thing. In our metric, 80% of the people are adequately prepared for retirement.”

Calculating how much you’ll spend in retirement (and how much you need to save for retirement) is no easy task.

In the absence of creating a year-by-year budget, many are told to use a time-honored rule of thumb: Plan on spending about 70% to 80% of your preretirement income in retirement. But that rule of thumb is not enough. “Just saying over and over again, you need to an income replacement rate of 70% is not helpful,” said Hurd.

Plus, that rule of thumb can lead to imprecise results.

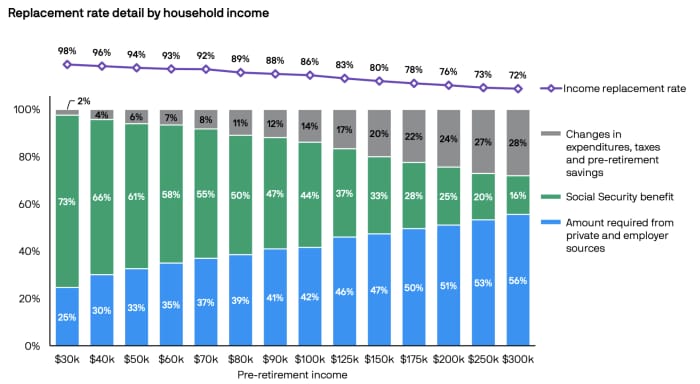

For one, income replacement rates vary widely by household income.

Consider this: Those with preretirement income of $30,000 replace 98% of that income in retirement, the bulk of it coming from Social Security, according to the 2022 Guide to Retirement, which is published by J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Those with preretirement income of $300,000 replace 72%, the bulk of it coming personal savings. And those with preretirement income of $150,000 replace 80%, a mix of personal savings and Social Security, and changes in expenditures. (See below.)

David Blanchett, then director of retirement research at Morningstar Investment Management, also concluded in 2013 paper that actual replacement rates are likely to vary considerably by retiree household, from under 54% to over 87%. Read Estimating the True Cost of Retirement.

J.P. Morgan

What’s more, the 80% rule of thumb doesn’t consider that your spending will decline on a real basis over the course of your retirement. The notion that you would spend the same amount at age 90 as you did at age 65 just doesn’t happen empirically, said Hurd.

“Obviously, over time you change, the circumstances of your life change,” he said. “Why would you ever think you’re going to keep spending the same as you did earlier in life?”

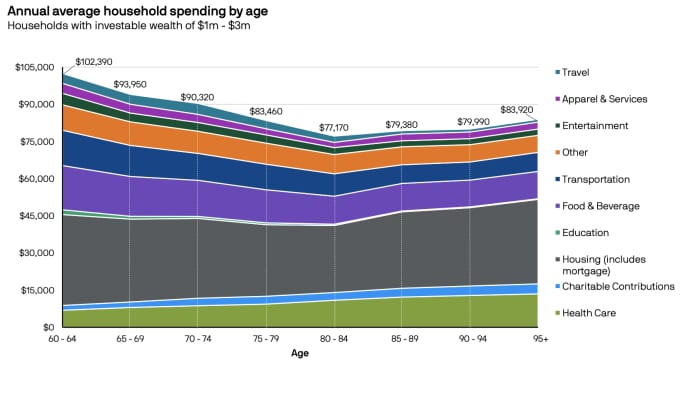

In its research, J.P. Morgan also found that spending declines on an inflation-adjusted basis. Its research shows that partially and fully retired households with investible wealth of $1 million to $3 million spend on average $102,390 between the ages of 60 to 64. That spending then declines to $77,170 for households between the ages of 80-84 and then it rises slightly to $83,920 for households age 95-plus. (See below.)

“Retiree expenditures do not, on average, increase each year by inflation or by some otherwise static percentage,” Blanchett noted in his 2013 paper. “The actual ‘spending curve’ of a retiree household varies by total consumption and funding level.”

J.P. Morgan

Other researchers also show that spending declines over the course of retirement. For instance, a recent Center for Retirement Research at Boston College study shows that spending declines for households as a whole, though wealthier and healthier households have relatively flat consumption.

Read: How much do retirees want to consume?

There is, of course, the 1965 paper that first reported that retirees would spend less in retirement as they age, Uncertain Lifetime, Life Insurance, and the Theory of the Consumer by Menahem Yaari, an Israeli economist professor.

Why the decline in spending?

So, what accounts for the decline in spending in retirement?

In an interview, Hurd said much of the decline is related to shifts in spending. During the early phase of retirement, what some call “the go-go years,” retirees spend money on travel, dining out, transportation and other categories. But over the course of retirement, they spend less and less on those categories more on healthcare and donations and transfers as a fraction of total spending. And it’s not necessarily due to budget constraints.

The increased spending on healthcare is “probably more modest than most people would think,” said Hurd, noting that spending on healthcare rises from about 10% of expenditures at age 65 to 15% for those in their 80s. “It’s an increase but it’s not as if people are spending all of their resources on healthcare.”

Ultimately, the changes in spending can be explained by “a change in taste and interaction with health” as well as one other factor that Hurd refers to as “been there, done that.” If you’ve already been to Italy 15 times, what’s the benefit of going again? In fact, many retirees as they age get less enjoyment from doing certain activities then they used to and that explains much of the decline in spending.

“Individuals gain less utility or happiness/satisfaction from consuming things as they age,” Blanchett said in an interview.

The decline in spending can also be explained by changes in a household; the death of a spouse, for instances, reduces expenses.

How much income should you plan for?

Hurd also unequivocally rejects using a fixed portfolio withdrawal rate such as the time-honored 4% rule to generate income in retirement.

“It doesn’t make sense because what you want to do is to take out money as you need it for your spending needs,” he said. “There’s no reason it should be a fixed amount of what you have. You take it out according to what you need and what you want to spend.”

Blanchett offered this advice: if you assume inflation will be 3% per year, maybe only assume that your spending will only increase by 1% or 1.5% per year. And, for many people, that increase can be offset by Social Security benefits, which are linked to inflation. As for withdrawals from your portfolio, he said that could be a fixed amount rather than one adjusted for inflation.

And the net effect of this approach is that you’ll “free up a lot of money for someone to do more earlier in retirement,” he said.

How much to save for retirement?

How might you plan for the decrease in spending while saving for retirement?

If you’re saving for retirement you need to understand better what your spending desires will be in retirement, how much you need to have, Hurd said. “Obviously, that’s not an easy thing to do…In fact, it’s a very hard thing to do.”

Is it better then to over-save while working? After all, you can’t back to work at age 80 if you suddenly discover you don’t have enough income to support your desired standard of living. However, you can alter your behavior as new information becomes available to you, Hurd said. You can adjust your spending. You can replace your car less frequently or downsize your home. “Humans are very adaptable,” he said.

And therein lies the answer to the question: How much to save?

“We need, obviously, to weigh that off, the expected hit to utility or well-being in old age from making that adaptation to the increased saving that would be required during working age to fend off that adoption,” he said. “And that’s the trade-off that we need to be thinking about.”

Given how difficult it is already for many to save for retirement during their working years, asking people to save more for “eventualities that may or may not happen to them in 30 or 40 years is the wrong to ask,” said Hurd. “It’s a hard life for a lot of people when they’re working and to tell them they need to save more for retirement is something that we ought to be very cautious about doing.”

Blanchett doesn’t share that opinion. “I would tell people to save more because they’re not saving enough,” he said. “I think collectively people should be saving 15% all in.”

He did note that current retirement models should be adjusted to account for the fact that retirement might not be as expensive as it’s currently conveyed.

The bottom line

So, what’s the standard you should be seeking given that your expenses will decline in retirement, and you’re not sure how much to save for retirement?

The ideal, said Hurd, would be to as well off in retirement as you were during your working life. And know that you will not spend as much in old age as you spent when you were at the beginning of your retirement years. And two, you’re adaptable. And three, your satisfaction with retirement – assuming you’re in good health and/or not widowed–won’t decline with age, even as your spending declines.