This post was originally published on this site

It’s often darkest right before the dawn.

That’s worth remembering, since consumer sentiment has plunged. The University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment has fallen more than 25 percentage points over the last year—one of its biggest 12-month declines since 1952, when the survey was first conducted. There have been only seven occasions since then in which the index fell more than that in any given 12-month period—once per decade, on average.

Fortunately, however, plunging consumer sentiment need not be the kiss of death for the stock market. If anything, it slightly increases the odds the stock market will produce handsome gains over the coming year.

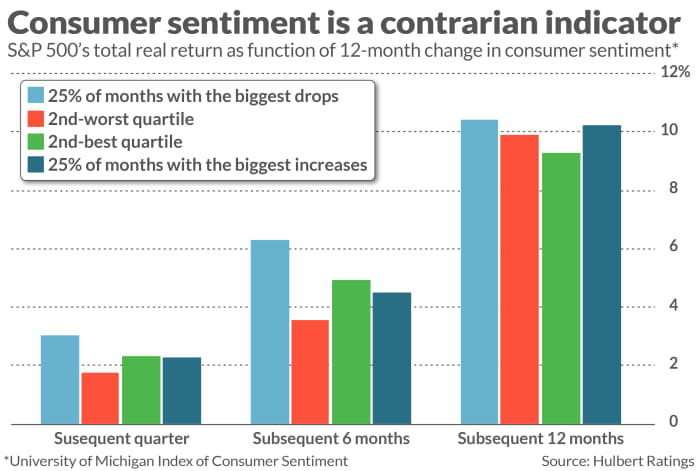

I summarize the historical record in the accompanying chart, which reflects data back to 1979, which is when the University of Michigan began conducting the survey on a monthly basis. The chart focuses on four different groups of months since then, sorted according to how much the University of Michigan index rose or fell over the trailing 12 months. Notice that, on average, the S&P 500’s

SPX,

best total real return came in the wake of the 25% of months in which consumer sentiment was the furthest below where it was 12 months previously.

In other words, consumer sentiment appears to be a contrarian indicator. When things start to turn sour, consumers exaggerate and become overly pessimistic. That causes the stock market to decline more than is justified, which in turn creates the preconditions for the market to produce above-average subsequent performance.

Inflation

One big reason why consumer sentiment has soured over the last year is the spike in inflation. It’s worth focusing on consumers’ reaction to inflation, since it helps to explain why consumer sentiment is a contrarian indicator.

Consumers have a tendency to extrapolate the recent past when forming their expectations of future inflation. That is, when inflation is low, they expect it to stay low. And when inflation worsens—like it has over the last 12 months—consumers expect it to stay high for at least a while longer. As a result, consumers will be most wrong at turning points—with their inflation expectations highest at the very point it’s about to come down.

This is exactly what contrarian analysis would expect. And it’s confirmed by the data.

To show this, I calculated a statistic known as the correlation coefficient, which represents the degree to which changes in consumers’ inflation expectations are correlated with subsequent changes in the CPI. The correlation coefficient ranges from a theoretical maximum of 1.0 (which would mean that the two series move in lockstep with each other, zigging and zagging in lockstep) to a minimum of -1.0 (which would mean that the two data series are inversely correlated, with one zigging while the other is zagging, and vice versa). A correlation coefficient of 0 would mean that there is no detectable correlation between the two data series.

Over the last 20 years, there is a minus 0.45 correlation coefficient between consumers’ inflation expectations and the CPI’s actual subsequent changes. That is a significantly inverse correlation. (More details are provided in a column I wrote last summer.)

Many have already weighed in on the debate over whether inflation will recede in coming months. The analysis presented here adds an additional perspective, suggesting that because consumers currently believe inflation will stay high is a reason to suspect it won’t.

The bottom line? Keep your pessimism in check. Left unchecked, you’re more likely to do something rash that you will eventually regret.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.