This post was originally published on this site

One of the most frustrating realities of the U.S. criminal legal system is that a person can be arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced in less than two years. Yet it takes years, decades, sometimes never, to correct a wrongful conviction.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, the average exoneration occurs almost 11 years after the conviction. Before this, who pays the costs, over many years? The families of the wrongfully convicted and communities, by way of U.S. taxpayers.

In 2020 alone, 129 men and women were exonerated from U.S. prisons. The years they lost to wrongful imprisonment total 1,737 — an average of 13.4 years per exoneree. A number of exonerations have been covered in the media, with some even becoming subjects of movies and television miniseries. What is not depicted on the screen is the crippling effects their wrongful imprisonment has on exonerees’ families and communities, and their struggle to reintegrate back into society after release.

As someone who was wrongfully convicted, and who has gone from being exonerated to becoming an attorney who works to exonerate others, I have personal experience with the economic chokehold placed on the families and communities of the wrongfully convicted.

I currently represent a man named Troy Ketchmore, who was recently paroled after 26 years in prison for a crime he has always maintained he did not commit. While working on Troy’s claim of actual innocence, we were indeed able to discover new forensic evidence to support Troy’s claim.

After almost two years of advocating for Troy’s early release, along with the support of the victim’s family and the Commonwealth of Virginia’s office, which prosecuted the case, a parole board granted Troy’s release.

Troy continues to pursue his claim of innocence. Meanwhile, the Ketchmore family is dealing with financial strain endured over the 26 years of Troy’s incarceration. During that time, his mother had exhausted her retirement fund on legal fees, prison phone calls, traveling for prison visits and helping to raise her grandchildren whose father was in prison fighting to prove his innocence. When the funds depleted, his mother sold her home and made other strenuous decisions trying to fight a system that had torn her son from her life.

The U.S. criminal legal system has drained so many other families like the Ketchmores — including mine. My mother was forced to dip into her retirement fund to finance the various expenses associated with my incarceration.

As co-founder of Life After Justice, a nonprofit that handles a limited number of actual innocence cases, I understand firsthand that there are not enough resources, attorneys, and organizations to handle the thousands of claims of innocence each year. The Exoneration Registry estimates that between 2% and 10% of the 2.3 million people currently incarcerated in the U.S. have been wrongly convicted. If there are, at a minimum, roughly 46,000 innocent Americans locked away, then 46,000 families and their communities are paying the cost.

We all pay the cost

In 2017 the Prison Policy Initiative found that mass incarceration costs U.S. taxpayers, state and federal government, and families of justice-involved people at least $182 billion every year. The wrongfully convicted are among them.

There are many costs to being convicted and serving a prison sentence. When a person goes to prison, so does his earnings and everyone who depends on them, including his community. “Costs related to moving, eviction, and homelessness for incarcerated individuals and their families, as well as the reduction in property values that may result from high rates of formerly incarcerated living in a particular area are estimated at $14.8 billion.”

Some studies suggest the cost of foregone wages while people are incarcerated, combined with the lifetime reduction in earnings after their release, is estimated at more than $300 billion annually. Any percentage of that estimated $300 billion owed to the wrongfully convicted is now a loss to the wrongfully convicted, their family, and the community.

Other social impacts of incarceration are equally devastating. Children of incarcerated individuals are five times more likely to go to prison themselves, compared with children whose parents are not incarcerated. Indeed, Troy’s oldest son is currently incarcerated and was not there to greet his father after 26 years in prison. Incarcerated individuals also experience higher rates of divorce and lower rates of marriage, which is estimated to reduce U.S. economic growth by $26.7 billion and increase America’s child welfare costs by $5.3 billion.

Reforming the justice system starts with providing resources and support to the families and communities who pay the cost of wrongful incarceration. These resources include access to mental healthcare, employment, and improved transportation, child care and schools.

What can we do to help?

- Pay it forward: Big law firms must start investing in Black and Brown communities and provide a pathway to careers in law and social justice reform.

- Community activism: Educate underserved communities on how to change policy on a local level.

- Provide services: Offer mental health treatment and social services to the families of the incarcerated, as we have started to do with our nonprofit LifeAfterJustice.org.

- Show us the money: Banks and financial institutions must lend to borrowers in Black and Brown communities so they can start business and invest in their children’s education.

Convergent Books

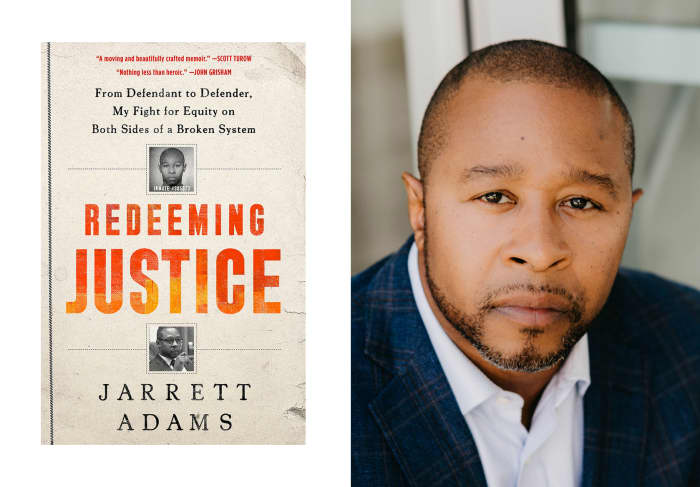

My own story is just the beginning, so I will close with a few lines from my new book, “Redeeming Justice: From Defendant to Defender, My Fight for Equity on Both Sides of a Broken System.”

“In the fall of 2017 . . . I decide to start my own practice. The Innocence Project takes on cases based on DNA evidence. I’ve learned that a number of wrongful convictions are simply not DNA based. I see a need to venture out and tackle those cases as well. I know that starting my own practice is risky, that you don’t make big money by righting wrongful conviction cases. I’m not looking to make a killing. I’m looking to make a living. I need seed money, but not one bank will give me a loan. I can’t prove that the color of my skin has anything to do with loan officers turning down my applications, but I don’t meet one loan officer who looks like me . . . “

Jarrett M. Adams is a defense and civil rights attorney and the author of “Redeeming Justice: From Defendant to Defender, My Fight for Equity on Both Sides of a Broken System.” (Convergent Books, 2021). Adams is co-founder of Life After Justice, a nonprofit dedicated to preventing wrongful convictions and building a system of support and empowerment for exonerees.