This post was originally published on this site

I believe I will live well past the age of 100, 150 or even beyond. I believe that you will likely live this long as well.

As it happens, more of us are already living well past our 100th birthday than ever before in human history. Our average lifespans have risen by decades in just the past half century. What’s more, the technologies that will add these extra, healthy years to our lives already exist.

Still, it feels almost crass to consider the coming longevity boom when the world is still in the throes of a pandemic that has claimed millions of lives and caused a decline in life expectancy in many countries, including the U.S.

It might also seem exactly the wrong moment to talk about our lives getting longer when the world faces extreme temperatures and untold suffering as the climate changes and the Earth warms.

Reframing our thinking

Yet, it is precisely because of these grave threats to humanity that we must begin seriously grappling with longevity — it is, in so many ways, the key to reframing our thinking surrounding many of our most persistent problems, starting with one of the greatest problems of all: How we approach our health.

Health-care systems throughout the world face a similar dilemma, which is how best to deliver an equal level of care to individuals throughout society.

In the U.S., this inequality can be particularly stark. A 2019 study published by JAMA drew on survey data from the CDC from 1993 to 2017, and found that, while all Americans’ self-reported health had declined in that time, white men in the highest income bracket were, overall, the healthiest, while poor minorities reported the lowest health overall. In fact, the study found that the gap between rich and poor Americans and their health outcomes was widening, with the widest of all gaps in groups that were poor and not white. These results are supported by other, even more recent studies, such as one, published in the journal PNAS, which found that the Black-white life expectancy gap grew by nearly a year and a half in 2020, from 3.6 to 5 years.

Addressing such unequal outcomes in our health systems is of the highest import, and one way to begin to do it is by thinking about individuals’ overall health and longer-term, lifespan health outcomes. As the PNAS study shows, comparing life expectancies of different groups can be terribly revealing. What if we transformed our health-care system to be geared toward promoting human longevity, with the key goal being — across all demographics — to extend life expectancy?

New technology

We can already begin to see the effects of a restructured system such as this one by the extraordinary deployment of a new technology on an underserved population, in the story of Victoria Gray and her sickle cell anemia.

The hereditary trait that causes sickle cell disease affects tens of millions worldwide, including as much as 30% of sub-Saharan Africans, and up to three million African-Americans. The bone marrow of those with sickle cell disease produces abnormally shaped red blood cells that are unable to carry oxygen to the body, which often leads to fatigue and frequent infections. In severe cases like that of Victoria, the disorder also causes sudden and excruciating bouts of pain. It also leads to premature death. The average life span for those suffering sickle cell is just 54 years old. In 2019, when she was 34 years old, the condition had grown so dire, she could no longer walk or feed herself. Emergency room visits and prolonged hospitalizations and blood transfusions were the norm. More than a nuisance, her inherited disease was a death sentence.

Until, one day in 2019, doctors at the Sarah Cannon Research Institute (SCRI) in Nashville, Tennessee, threw Victoria a lifeline. She became the first patient to receive a new form of treatment for hereditary diseases. Doctors at the SCRI removed bone marrow from her body and altered the genes of her cells using a new technology called CRISPR-Cas9. The procedure effectively edited out the defects in her genes that caused sickle cell, then reintroduced billions of enhanced cells back into her body. One year after the treatment, Victoria appeared to be doing marvelously. When researchers checked nine months after initial treatment, the vast majority of bone marrow cells and hemoglobin proteins found in her body appeared to be functioning effectively. More importantly, her pain attacks and hospital visits were a thing of the past.

It is perhaps too early to declare this procedure a cure for all sickle-cell disease, but it has for the moment completely altered the life of one person. It also gives us a glimpse into the future, into a whole host of treatments we can now produce by directly altering our genomic code. Humanity is on the verge of a fundamental health transformation with this new toolkit, and this revolution will allow us to treat or even cure previously untreatable diseases — many of which have long ravaged underserved populations. By thinking about ways to extend everyone’s life, we can deliver better health care for all.

‘Silver tsunami’

There is, of course, the persistent fear that extreme longevity will leave most of us — and the Earth — in ruin. But statistics tell a different story. The world’s population is on track to “stop growing by the end of this century,” according to 2019 analysis by the Pew Research Center. A 2020 study by The Lancet projected that the global population will not just stop growing; it will begin shrinking — from around 9.7 billion people in 2064 to just 8.8 billion by 2100. There are more people over 65 than under five in the world — a first in recorded history. This trend is what demographers refer to as “the silver tsunami,” and it is going to have enormous economic and social ramifications for everyone and everything on our planet. The longevity revolution is already creating a seismic shift in life on Earth. We would be wise to begin preparing for this shift now.

Preparing for the longevity revolution requires us to think long term, which is not something humans are generally very good at. Still, we must try. So many of the blind spots and weaknesses in our society were revealed by the pandemic, and so many of these had to do with our inability to think longer term. By thinking longer term, we might begin to transform our world today, and make us all healthier in the process. It is, quite simply, our moral duty.

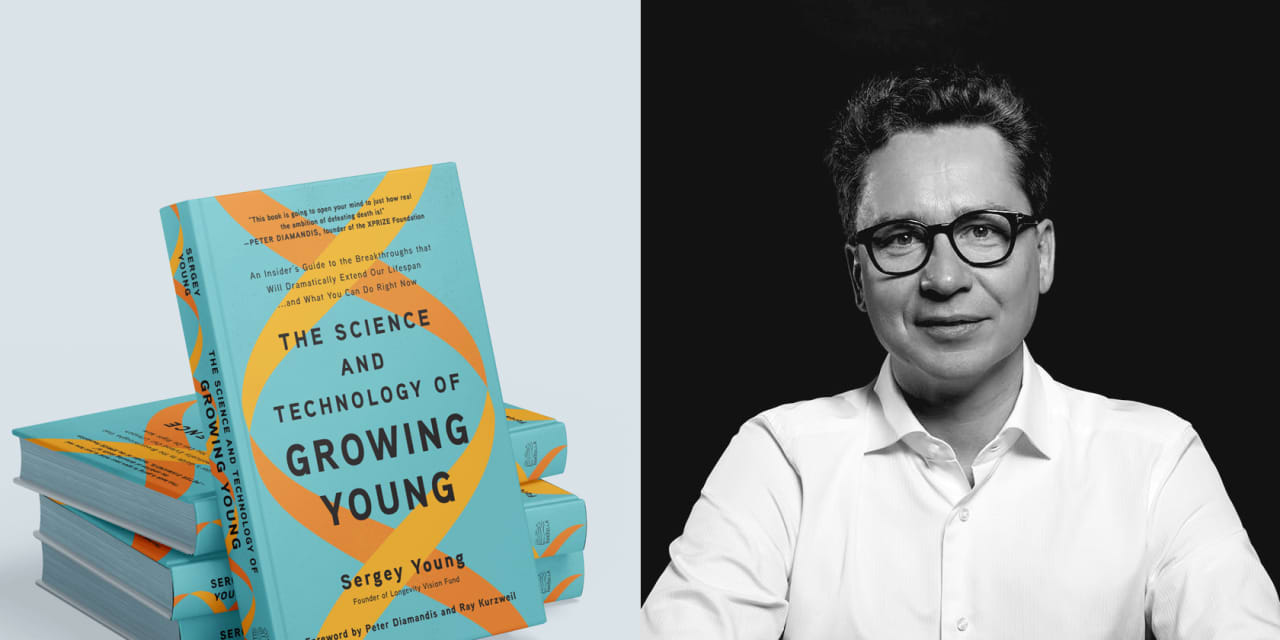

Sergey Young is a longevity investor, the founder of Longevity Vision Fund and author of the new book “The Science and Technology of Growing Young” (BenBella Books).